Printable Version of Topic

Click here to view this topic in its original format

Unmanned Spaceflight.com _ Opportunity _ Victoria Annulus

Posted by: RNeuhaus Aug 9 2006, 01:41 AM

From today, Oppy will start to head toward the Victoria Crater which is about 500 meters away. The drive would take about one month (that is 15 soles of driven with an average of 33 meters/sol, the other 15 soles would be for other purposes or restrictive soles).

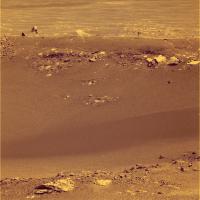

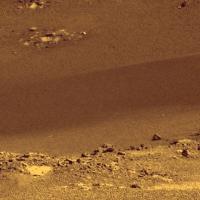

The surface around Victoria Annulus, I seems it won't be as smooth as the way between Eagle and Endurance craters but the surface would have no uniform or parallel wave of sand and dust in small size of ripple. http://www.unmannedspaceflight.com/index.php?act=Attach&type=post&id=6910, http://www.unmannedspaceflight.com/index.php?act=Attach&type=post&id=6804

Otherwise, the surface might have ripples smaller and alike to the ones of El Dorado, on the skirt south side of Columbia Hill. Besides, the Anuulus has no outcrops except to around of few small mini-craters.

This is a change of morphology of surface around the Victoria Annulus. What does it explain about this developing kind of surface of sand? Its extension is just around the inside of Victoria's ray of ejection. That is coincidence. Around that has no bigger ripples as the outside of Annulus.

The explanation would be that around annulus has smoother rock or outcrop surface, no blocks which had not helped to build ripples by the winds. Other factor, I am not sure, is that the slope from the border of Annulus to crater is positive (going up by few meters), then this might be another factor not to build ripples. I have seen that anywhere in the desert that have a slopes does not have any ripples but only flat surface.

Any debate about why the Victoria Annulus does not look like ripples as the outside of Annulus.

Rodolfo

Posted by: Analyst Aug 9 2006, 06:46 AM

I am not sure we are done with Beagle yet. I hope we are not, there is so much to learn, more IDD work etc. No need to rush.

Analyst

Posted by: djellison Aug 9 2006, 07:06 AM

Indeed -there is intended investigation of the things around Beagle before heading off again - RN - you've jumped the fun in a serious way ![]()

Doug

Posted by: RNeuhaus Aug 9 2006, 02:08 PM

Doug

Yes, I forgot that Oppy has to collect more data around Beagle. The earliest date to leave Beagle would be after August 15.

Rodolfo

Posted by: Nirgal Aug 10 2006, 06:40 AM

Re. the Apron/Annulus: Apart from the orbiter images, I wonder how much can be learned from the

recent set of Pancam shots in the potential drive direction so far wrt. to driveability / dune heights,

surface material etc. of th Apron area ?

Posted by: WindyT Aug 13 2006, 04:56 PM

Let's not forget the slightly arcane math question that might be answered by those so inclined:

What's the approximate value in cubic meters of material excavated by the crater, and does it approximately match the Victoria Annulus (the ejecta apron material)? Several assumptions would have to be made about the height profile(s) of ejecta material, and I suppose we'll eventually get to see some interpretations using cross sections at some future date.

I'll add a couple more questions I don't necessarily want answered, but did want to idly ask:

While I'm assuming the answer would be "Not enough information to tell, but probably, 'NO'", is it possible for a measurable fraction of this evaporitic material to really have been be "vaporized" by the initial impact to the extent that it's missing from the ejecta apron material and the surrounding region?

How much got powdered just enough to have been a significant fraction of the dune material outside the annulus that Oppy has been traversing for the last several months?

Posted by: algorimancer Aug 13 2006, 08:22 PM

What's the approximate value in cubic meters of material excavated by the crater, and does it approximately match the Victoria Annulus (the ejecta apron material)? Several assumptions would have to be made about the height profile(s) of ejecta material, and I suppose we'll eventually get to see some interpretations using cross sections at some future date.

We'd need a detailed topographic model of the entire crater and ejecta (or at least a good quadrant of it) before we could answer that question. I'm not confident that we will manage better than a ballpark figure. Sounds like a good student project, though

Posted by: dvandorn Aug 13 2006, 09:33 PM

It's also very difficult to estimate the amount of material that was exhumed and deposited around Victoria. You would have to have a good topographic map of the contact between the ejecta blanket and its underlying layer. While this *might* be deduced from a seismic study of the neighborhood (the debris usually has more voids and more lower-density inter-boulder fill within its mass than the underlying pre-impact surface, and therefore has a different seismic signature), I don't think you could do much more than a WAG from the photo evidence.

I don't have the relative figures at hand (and it does vary by impact-target composition), but a certain amount of the target, and nearly all of the impactor, are usually vaporized at the moment of impact -- especially for a crater the size of Victoria. That vaporized material is sprayed in tiny droplets around the local area, and on planets with atmospheres, can be spread preferentially on the prevailing winds. *

As you reach the edge of the region in which the impactor and some of the target are both vaporized, heat and pressure are high enough to melt the rocks. This melt takes on the geochemical characteristics of *all* of the rock types that exist within the melt region of the impact event. It takes on the physical characteristics of igneous rock. This type of rock is typically called an impact melt.

Further out from the center of the blast, the temperatures and pressures decrease through the ranges at which some rock types melt, some are shattered into a fine dust, and others remain resistant to complete destruction. Those pieces which do not melt or shatter become clasts, embedded in a matrix of more easily melted rock. These are fine-clasted breccias -- the clasts in these breccias can be very tiny, indeed.

Even farther out, the impact melt and fine-grained breccias generated closer in to the blast are rapidly propelled through a portion of the target that is broken up, but not melted or pulverized. The still-liquid melts from closer in grab up these cooler rock pieces and make large-clast breccias. In many cases, the clasts in these breccias are pretty much pristine and unaltered examples of the rock that was originally swept up by the melt flow.

These are the kinds of things we ought to be seeing in Victoria's annulus as we traverse it. However, the fact that the Victoria area may well have had an active water table during or after the emplacement of the debris blanket muddies the waters (pardon the pun). The landscape has undergone massive aeolian erosion since the impact, and has possibly (but not definitively) undergone aqueous alteration since then, too. So the rocks will not necessarily resemble the examples we've seen of impact melts and breccias on Earth and the Moon.

* - In re the vaporized material -- it occurs to me that if there was any way to detect the extent of the deposition of vaporized elements from a given impact, we could back-model the atmospheric effects and set some limits on the nature of the atmosphere at the time of the impact. For instance, how thick it was...

-the other Doug

Posted by: Bill Harris Aug 13 2006, 10:08 PM

You are correct, without topo and gridding data/capability, these volumetric estimates will be no more that a very WAG. But let me work up some back-of-the-envelope scribbles: Victoria diameter= 750m, depth=120m, ejecta blanket breadth=600m and ejecta blanket depth at crater rim=10m (or less). These are first guess dimensions of Victoria, we can refine them as we can.

Very good discussion, Doug. The impact will alter the rocks depending on the energies involved. This is one reason why I've pushed to get closer looks at the dark boulders and cobble fields we've seen along the way: these are peeks into the cauldron of the Victoria impact. Gathering this data along the way is critical because once we are on the apron and at Victoria the world changes.

--Bill

Posted by: WindyT Aug 14 2006, 03:43 AM

Oh, excellent, thanks! I was a bit afraid to ask about the current speculation on whether there was an active water table when Victoria was formed -- Is this the so-called "Splat!" scenario I've heard referenced to?

Posted by: Bill Harris Aug 14 2006, 09:08 PM

Here are initial (and very WAG) guesses on the volumes of Voctoria and the ejecta blanket, based on the numbers above:

crater 18x10^6 m^3

ejecta 10x10^6 m^3

or, roughly, the ejecta is half the volume with a rim thickness of 10 meters or therefore roughly an equal volume at 20m thickness.

Your guess is as good as mine...

--Bill

Posted by: dvandorn Aug 15 2006, 06:45 AM

And, like I said, Bill, the composition of the impact target makes a big difference in how much of the target is vaporized, how much melts, etc. If, for example, the target were mostly jarosite, or there was a thick layer of fairly pure jarosite, it would go from vaporization to pulverization with little melting in between. Some rock types simply don't melt in their primary form -- they pulverize into dust instead. And volatiles content affects the amount of mass vaporized, as well...

However, I rather doubt there was so much jarosite in Victoria's target as to inhibit widespread melting. My understanding is that the jarosite we've found is mostly in the blueberries, and the blueberries do not represent a large percentage of the evaporite down in this terrain. Though, if the blueberries resisted melting and were pulverized into sand and dust instead, that could explain the dark, smooth sandsheet remnants of the annulus.

-the other Doug

Posted by: Bill Harris Aug 16 2006, 06:14 PM

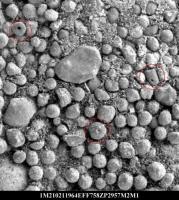

Oppy is currently in the transition zone between the ripples and the apron and has done some IDD work: a series of MI and an MB on the ripple face that she turned on and backed up to on Sol 909.

Visible are the subrounded-to-subangular fine gravel-sized particles, plus angular fragments that look vesicular plus well-rounded granules, some of which might be hematite concretions. And, I may be jumping the gun on this, I think I see discrete sand-sized particles (and not silty clumps). We're statring to see changes in the ripple material.

http://qt.exploratorium.edu/mars/opportunity/micro_imager/2006-08-16/1M208968686EFF748BP2936M2M1.JPG

--Bill

Posted by: djellison Aug 16 2006, 07:50 PM

Wow - nice MI sequence.....trying to merge with Pancam now ![]()

(nope - can't match with PC - it's all too samey)

Posted by: RNeuhaus Aug 16 2006, 08:06 PM

(nope - can't match with PC - it's all too samey)

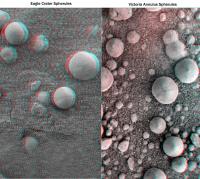

Almost full of spherules on the Annulus? They are back again as full since Eagle Crater.

Rodolfo

Posted by: Tesheiner Aug 16 2006, 08:08 PM

I suppose MMB can help. If not, pointing data on the data tracking web.

Posted by: djellison Aug 16 2006, 09:09 PM

I don't believe any placement info for the MI is involved in the PCDB

Doug

Posted by: Nirgal Aug 16 2006, 09:29 PM

(nope - can't match with PC - it's all too samey)

very nice MI stitch, Doug !

couldn't resist doing a quick colorization of this one:

http://mitglied.lycos.de/user73289/misc/oppy_m909_col_a.jpg

Posted by: dvandorn Aug 17 2006, 12:01 AM

I would be really interested in seeing the mini-TES runs as we have approached the annulus and as we embark onto it. If the annulus is primarily hematitic, we ought to be able to determine that fairly easily with the mini-TES.

What will be very interesting is if the annulus does *not* appear very hematitic to the mini-TES...

-the other Doug

Posted by: Bill Harris Aug 21 2006, 05:44 PM

Here is the current PanCam view of the sand at our feet/wheels, I'm thinking Sol 914 or so. There is an interesting change in the surface texture-- I can still make out the rounded granules but I'm seeing either angular fragments or flat areas with angular borders between between the granules.

Fooey. Nothing _on_ the ejecta apron, yet, this is from Sol 912 and is an L257 of the ripple trough we were at a couple of Sols ago...

--Bill

Posted by: hortonheardawho Aug 21 2006, 08:01 PM

4 frames of sol 910 MI pan near Mossbauer press colorized:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/hortonheardawho/221270069/

Posted by: Bill Harris Aug 21 2006, 10:40 PM

Whew, who said flat as a pancake! Here is an L7 Pancam from today showing aeolian and (possibly) anatolian features. I _think_ I have the location spotted on the MOC image, let me post this and go offline to check.

--Bill

Posted by: djellison Aug 21 2006, 11:05 PM

That's several sols old....

Sol 912 - 10:38am

Doug

Posted by: mhoward Aug 21 2006, 11:12 PM

--Bill

That's "Espanola" (East Hillock) in the forground, and ol' "Jesse Chisholm" in the background, on Sol 912, I believe. A 'Kodak' moment.

http://www.flickr.com/photo_zoom.gne?id=221465641&size=l

Posted by: Bill Harris Aug 21 2006, 11:26 PM

Well, duh. You're correct; I was thinking that these "new images" were further along than they were.

Anticipation, I guess.

--Bill

Posted by: CosmicRocker Aug 22 2006, 04:23 AM

When I saw that sol 912 L7 during my morning MMB update, I nearly jumped out of my seat. I had been waiting for a nice view of the step up to the edge of the apron, and was wondering why we hadn't yet seen a more impressive view of it. At least, that is what I interpret Espanola, and I suppose Jesse Chisolm to be now. Stratigraphically, it looks just like the Halfpipe formation, complete with the overlying layered ripples. The 3D view of it is impressive. As we drove further onto the apron I was seeing all of the dark pebbles between the sparse ripples and wondered why. I was expecting the apron to be totally different. I'll take my geologizing over to the halfpipe topic now.

Posted by: mhoward Aug 22 2006, 05:04 AM

A quick stitch:

http://www.flickr.com/photo_zoom.gne?id=221741629&size=l

Posted by: Bill Harris Aug 24 2006, 01:47 PM

In the lastest Navcam pans, we can see a light-toned area extending to the SE in the direction of Victoria's rim, and this area corresponds to the light-toned area between the windgaps in the crater rim visible on the MOC Route Map image. Close in, we can see that this light-toned material seems to be associated with the transverse ripples caused by the SE wind and we can assume that this light-toned material is likely eroded evaporite material from the rim of Victoria. I'd guess that the prominent dark streaks we see on the ejecta blanket are simply the absense of the light-toned dust. We'll see a a couple of Sols.

http://www.unmannedspaceflight.com/index.php?act=Attach&type=post&id=7128

--Bill

Posted by: jamescanvin Aug 25 2006, 01:56 AM

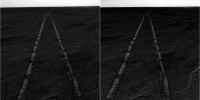

Just been looking at the tracking site for tosol (919) and I see we have this:

Looks like we're going to put a trench in the annulus over the weekend.

Does anyone know if Oppy has done any (intentional

Should be an interesting weekend.

James

Posted by: Tesheiner Aug 25 2006, 06:12 AM

> Does anyone know if Oppy has done any (intentional ) trenching since the the steering motor failure?

I was ready to say "Yes!", but then I saw the "intentional". ![]()

Posted by: Bill Harris Aug 25 2006, 12:57 PM

It gets more interesting on the ejecta apron. Looking at Phil Stooke's polar of mhoward's Sol 917 pan we can see a network of polyagonal traces on the surface. These traces are a darker and possibly coarser material evidently outlining paving stones of evaporite. The shape is reminescent of the jumbled and eroded blocks we saw around Endurance crater; they seem too irregular and too large to be the typical "mudcracks" we see on the evaporite surface. And the outlining traces seem to have a light-toned core. Hopefully we'll get a series Pancam closeups of these features and this won't be a drive-by sighting.

So it might be that the lighter tone of this location is not totally due to the windblown evaporite dust as I noted a couple of posts up. Based on what we see here, the sandy ejecta soil is quite thin at this spot, so there may be more to the story.

http://www.unmannedspaceflight.com/index.php?act=Attach&type=post&id=7144

--Bill

Posted by: RNeuhaus Aug 25 2006, 02:31 PM

The surface is so "ironed". Very plane and smooth to ride a surf. The surface has very fine grain covered by small spherules.

Enclosed pictures of Sol 918.

http://marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov/gallery/all/1/n/918/1N209680180EFF755JP1785R0M1.JPG

I think that picture is pointing to South azimuth.

http://marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov/gallery/all/1/n/918/1N209680385EFF755JP1785R0M1.HTML

It is evident the surface has the erosion caused by the aeolian force.

Probably of North azimuth view.

Rodolfo

Posted by: Bill Harris Aug 25 2006, 11:08 PM

Here is an L257 Pancam of the spot that Oppy trenched on Sol 918 We don't have a color Pancam of the tranch yet, but I've included an L0 Navcam of the trench. The granules look like Blueberries and the sand is well-compacted/indurated or is a very thin layer. Nothing out of the ordinary jumps out at me, but maybe we'll get some MIs of the soil here.

--Bill

Posted by: RNeuhaus Aug 26 2006, 12:04 AM

This kind of surface is very easy to drive as off-road. Is indurated and compact as Bill has said. It seems like that the surface has undergone a process of some kind of cementation caused by some kind of chemical reaction.

Do you have any idea about why the surface has got indurated?

Rodolfo

Posted by: Bill Harris Aug 26 2006, 01:40 AM

I'm thinking that one sub-cycle of the Martian hydrologic cycle involves frost formation at night and when the frost is heated in the early morning it already in contact with a sulfate salt and briefly makes a saturated "brine" with a low freezing point which soaks the underlying sand and dust. The water quickly evaporates and the dissolved salts cement the sand. The quantity of water is very very small, but this can happen millions of times, daily, over thousands of years and build up to appreciable thickness. We've seen the duricrust almost universally on Mars.

There may be more to it, but this is the quick explanation of what appears to be happening.

--Bill

Posted by: Aldebaran Aug 26 2006, 03:10 AM

There may be more to it, but this is the quick explanation of what appears to be happening.

--Bill

Bill,

I may have said this before either here or on another forum, but the Martian regolith contains a high proportion of salts such as magnesium and calcium sulfates and chlorides. These are either anhydrous or monohydrates, such as Kieserite, MgSO4.H2O. My understanding is that the hydration state can change depending on the temperature, and it's a very complex multiphase system. I don't think it can get to the saturated brine stage, simply because there is too much 'dessicant'. I think of Mars in terms of a planet sized vacuum desicator. I've worked with vacuum dessicators in a lab environment, and strange effects can result from phase changes, without involving any free water being produced. These include the production of filament-like crystals among other things. The constant diurnal and season variation over a long timescale can produce such duricrust either without any free water, or at the very least, extremely thin films several molecules thick, due to non equilibrium effects.

Posted by: CosmicRocker Aug 26 2006, 06:02 AM

Well, all I can add to this discussion is that I was hoping we would not yet again see the apparently ubiquitous white stuff. I am not certain that we will really understand it until we dig enough to find and inspect its lower contact. I was hoping for a fresh and deeper roadcut, but apparently this material is quite compacted, and it is difficult to dig through. I discovered a wheel scuff done just prior to the arrival at Beagle. I forgot the sol, but it was only that, a scuff. It found the white stuff just below the surface. Some kind of dessicating salt model might work, but deeper observations are needed.

This is a fascinating planet. Just when you think you have a working model...Wham!

Posted by: Bill Harris Aug 26 2006, 09:34 AM

Aldebaran, your analysis is correct, I was having trouble expressing that. I believe that the interaction between water and salts is involved but there is not enough water involved to make liquid anything. I live in the humid southeast USA and many of my views are shaped by living in a dripping atmosphere. In my office I have a piece of pyritic sandstone where the pyrite is reacting with water (etc) to make iron sulfate salts (et al), which in turn pull enough water from the air to sustain the pyrite+water+air=nasty stuff reaction.

But this is the eastiest explanation of the duricrust.

Tom, I don't think we'll ever NOT see white stuff on Mars and even without seeing the chemistry of it I'd suspect that it is a sulfate salt. Sulfides weather to sulfates and unless you have a lot of water to carry it away the salt tends to accumulate. We've see the light-toned material in the looser drifts every time we've cut a trench to purgatory...

Looking at the recent Navcam images I notice that the wheel tracks are light-toned and I suspect that the sand is very thin at this location and we are seeing a reaction zone at the sand-evaporite contact. We need a RAT hole in the wheel scuff.

Again, speculation on my part based on a lot of visual cues/clues and minimal data. Still, the truth will prove to be stranger than reality here on Mars...

--Bill

Posted by: ElkGroveDan Aug 26 2006, 02:48 PM

I was wondering about that. Are we perhaps looking at sulfates at the tail end of this Viking 1 trench? (Or is it, in the words of Roger Daltry, "Just another trick of the light?")

(source: http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/jpeg/PIA00389.jpg)

Posted by: CosmicRocker Aug 27 2006, 06:31 AM

Do you have any idea about why the surface has got indurated?

Rodolfo

After looking back at many of the scuffs and trenches Opportunity has made along the way, I am nearly convinced that this white stuff is possibly best explained by some kind of a salt concentration mechanism, as it appears to be a horizon that cross cuts soil stratigraphy but is not continuous. The thing I am finding most interesting lately, is how looking back at old images leads me to new thoughts. It is very different from chasing the latest images for new thoughts. A lot of information has been collected that I had previously glossed over. There is still a lot of low-hanging fruit.

Posted by: Bill Harris Aug 27 2006, 09:25 AM

This is indeed the beauty of having a continuous organized record of mission imagery: if we see something that is significant, we can look back through the earlier images. For example, the surface here is similar to the material around Endurance but not identical. And why does the rippled (or drifting?) material behave differently?

We sometimes complain about not having access to the "chemistry" data, but that is the "meat" to many a paper and thesis so we'll have to be content with the pictorial side of the dataset.

--Bill

Posted by: Bill Harris Aug 31 2006, 03:38 AM

The first MI images of the ejecta apron beyond the rippled transistion zone are coming down to the Exploratorium. One of the early images is amazing-- there is clearly a bimodal distribution of the granule sizes; this speaks volumes about their origin.

More later...

--Bill

Posted by: glennwsmith Aug 31 2006, 03:51 AM

Bill, one never knows where to post. Re the MI image you have referenced, I would be very interested to know your thoughts on my latest posts in the "Victoria here we come . . ." thread . . .

Posted by: Gray Aug 31 2006, 04:50 PM

More later...

--Bill

Actually, Bill, I'd argue for at least a trimodal distribution. Don't forget the fines.

Were they deposited after the coarser grains; or do they represent incomplete winnowing of sediments that were deposited all at the same time?

Posted by: Bill Harris Aug 31 2006, 06:45 PM

Well, maybe, technically, but let's look at the granules and not the sands and the fines. So there. ![]()

The fines may turn out to be another issue.

Look at the trend to the larger granules to be pyramidal and not spherical or randomly sub-spherical. My initial thoughts are that these may be ventifacts since they seem to have a similar orientation. I'm thinking that the larger granules are "impact lapilli" or tektites, the basalt basal unit that has been melted, ejected and has formed droplets in free-fall. The smaller granules are hematite concretions, the standby Blueberries. The overlying evaporite unit was pulverized by the impact, thrown out as the ejecta apron where it weathered and eroded quickly, leaving the Blueberries behind. Methinks we'll find a lot of fragmented and residual evaporite under the desert pavement here.

My initial theory, but let's see what the Scratchplate shows. And we should be getting more MIs of the wheel trench this evening.

--Bill

Posted by: Gray Aug 31 2006, 07:41 PM

I agree with your prediction that the evaporite is probably not far below the surface here. But I'm not sure I agree that the "blueberies" would be durable enough to withstand the impact. We've seen examples of fractured 'blueberries" in other areas. An impact might pulverize them along with the evaporite. Could it be that the blueberries are a pre-impact lag deposit that survived the blast? If that's the case; and if the larger granules are tektites, we might expect to see a blueberry or two embedded in the underside of the larger granules. (If we could turn them over).

--lee

The larger granules which you suggest are tektites reminded me of taconite pellets, the rounded nodules of milled iron ore that are processed for shipping. I'm not suggesting a similar process for their origin - just an interesting coincidence of form.

Posted by: Nirgal Aug 31 2006, 08:49 PM

Here is a panorama of the latest MI in false colors showing the bi-modally distributed pebble field:

http://mitglied.lycos.de/user73289/misc/oppy_m924pan_col_d.jpg

Posted by: ugordan Aug 31 2006, 09:04 PM

Awesome! Normally, I don't care for colorizations, but one can actually believe the real thing would look like that.

Really great work, Nirgal!

Posted by: RNeuhaus Sep 1 2006, 01:12 AM

http://mitglied.lycos.de/user73289/misc/oppy_m924pan_col_d.jpg

Nice colorization! the image speaks more if it has color!

The picture image has called me more curiosity to see all of them. The stone which I suspected most is the ones biggest and with angular edges. However at the top, middle and right of the biggest stone looks like that it has "fossil" marks. Among the spherules, there is five broken spherules (below and left (2) and right (3) from biggest stone). Interesting!

Rodolfo

Posted by: Jeff7 Sep 1 2006, 03:17 AM

I find it interesting that so many of them seem to have a little point in the center, and generally facing up.

What else caught my eye: http://nasa.exploratorium.edu/mars/opportunity/micro_imager/2006-08-31/1M210211964EFF758ZP2957M2M1.JPG

Posted by: glennwsmith Sep 1 2006, 04:17 AM

Fantastic colorization Nirgal!

Posted by: centsworth_II Sep 1 2006, 05:40 PM

Thanks Nirgal, I now have a life-size bit of Mars sitting next to my computer.

Posted by: Gray Sep 1 2006, 06:44 PM

Very impressive Nirgal. What caught my eye was, just up from the lower left corner, is one of the larger grains with a smaller grain that appears to be embedded in it. ![]()

---lee

Posted by: tty Sep 1 2006, 06:51 PM

I noticed the same thing. They look like *very* small ventifacts. If so they must have been sitting there for a loooong time.

tty

Posted by: BEHSTeacher Sep 1 2006, 07:35 PM

What else caught my eye: http://nasa.exploratorium.edu/mars/opportunity/micro_imager/2006-08-31/1M210211964EFF758ZP2957M2M1.JPG

I see 3 with holes in them - so it can't be a camera artifact. Did someone break their necklace here?

Posted by: gregp1962 Sep 2 2006, 06:04 AM

Um, where are we?

http://qt.exploratorium.edu/mars/opportunity/pancam/2006-09-01/1P208086815ESF74ZTP2560R3M1.JPG

I thought we were a long ways from anything but, small dunes.

Posted by: bluemars1 Sep 2 2006, 06:16 AM

http://qt.exploratorium.edu/mars/opportunity/pancam/2006-09-01/1P208086815ESF74ZTP2560R3M1.JPG

I thought we were a long ways from anything but, small dunes.

That's from almost a month ago.

Posted by: MizarKey Sep 2 2006, 08:08 AM

Greg, that image, for me, was immediately recognizable as the far wall of beagle from the approach...I'd know that big slab anywhere ![]()

Posted by: SacramentoBob Sep 2 2006, 05:50 PM

We need a geologist to explain what the deal is with these "holy"rocks. What could be causing such perfect little holes? When I noticed just the one at the upper left, I assumed it was a camera artifact. I have to assume that we are looking at something that disolved out of the rock, or was created when the rock formed.

Any ideas? -

Posted by: RNeuhaus Sep 2 2006, 06:16 PM

The microcospic picture taken on scrapped track. It has no spherules but only fine grain -powder- and it is somewhat endurated.

http://marsrover.nasa.gov/gallery/all/1/m/926/1M210388035EFF758ZP2936M2M1.JPG

Rodolfo

Posted by: algorimancer Sep 2 2006, 09:09 PM

I see 2-3 ratted blueberries, plus 3 distinct horizontal layers. Looks like ratted evaporite to me.

Posted by: djellison Sep 2 2006, 09:15 PM

It's soil pushed flat by the mossbauer.

Doug

Posted by: glennwsmith Sep 3 2006, 04:26 PM

I hate to keep obsessing about this bit of conchoidally fractured pebble, but Nirgal's superb colorization adds to its interest. A fractured face is visible, while we can just make out the margins of the downward face -- and this would seem to indicate a patina typical of the alluvial (!) chert gravels found in abundance in, among many other places, my home state of Louisiana. So one thesis is that, among the layers disturbed by the impact which created Victoria, is bed of alluvial gravel !?! There are of course other weathering processes which can create patinas, but it is interesting to note the relative freshness of the fractured surface.

Posted by: RNeuhaus Sep 4 2006, 04:59 PM

Gleenwsmith: The stone is the original comparing to the rest. It has good edges, a fractured stone after so many years, between thousand millions and millions years. Very strong stone which has withstanded the aeolian and hydro erosion . About the chemical erosion not like to the spherules which is the product of the chemical process ![]() ?

?

I have enclosed a picture. The surface has a very fine grain that leaves the wheels neatly well marked.

http://marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov/gallery/all/1/p/928/1P210567239ESF758ZP2575L5M1.JPG

Rodolfo

Posted by: glennwsmith Sep 5 2006, 03:49 AM

Rodolfo, I am certainly agreeing with you if you are saying that the fractured stone is the result of different processes than those which resulted in the spherules. And nice picture indicating how spherules are sitting on top of a duricrust. . .

Posted by: dvandorn Sep 5 2006, 06:28 AM

I keep wondering if the specific forms we see in the soil right now (the granule size ranges, the organization of the granules into three basic sizes and shapes, color and hardness) can tell us something about the conditions of the impact target at the time of the impact.

Does any of the soil material suggest that the impact target was wet or otherwised volatile-enriched? I'm assuming that at least some of the granules we see are pieces of impact melt, and I suspect the conical "drops" that some have labeled tecktitic are the most likely candidate for being impact melts. Does their shape and size, and the nearly ubiquitous hole in the center, suggest anything about volatiles content of the target? Or about its composition? Do we have to assume that their present shape and distribution is the result of erosional processes, or is there anything of their formation still evident in what we can see?

Unfortunately, the three granule types seem so thoroughly mixed that it will be impossible for Oppy to get a good specific composition of just one of the types... ![]() so we'll have to infer composition of the various types from the aggregate Mossbauer and APXS readings we get from it. But I think that, if we could answer some questions about the constituents of this soil, we'd have some further insight into the chemical and climatic history of the region.

so we'll have to infer composition of the various types from the aggregate Mossbauer and APXS readings we get from it. But I think that, if we could answer some questions about the constituents of this soil, we'd have some further insight into the chemical and climatic history of the region.

-the other Doug

Posted by: Bill Harris Sep 9 2006, 10:19 AM

Finally, we got the makin's for L257 images of the current trench and skuff on the ejecta apron.

Doug, I haven't decided about volatiles in the impact target. We'll need to look into Emma Dean and specifically the evaporite chunks with the unusual texture and/or darker tone. Maybe we won't do a drive-by this time...

--Bill

Posted by: glennwsmith Sep 10 2006, 03:04 AM

john s -- sweet!

Posted by: CosmicRocker Sep 10 2006, 03:41 AM

That was freakin' brilliant! ![]() It is now my wallpaper. It makes me realize that before long we will have bootprints on Mars.

It is now my wallpaper. It makes me realize that before long we will have bootprints on Mars.

Posted by: Aldebaran Sep 10 2006, 03:49 AM

Any ideas? -

I'm not a geologist, but I minored in geology. Others have reported these holes. The best explanation I can find is that the concretions in many cases are associated with a network of dedos-like stalks. When the concretions are worn out of the rock, there is a tendency for these to snap off at the concretion, leaving a small indentation. We have noted the presence of these 'stalks' in several other locations, for example at the feature known as 'Pilbara' by Fram crater on the approach to Endurance. While wind erosion and chemical erosion certainly played a part in producing the stalks, there may be some evidence for a partial network of weakly indurated material within the matrix.

This MI image shows an example of such a stalk protruding from a spherule.

http://marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov/gallery/all/1/m/034/1M131212854EFF0500P2959M2M1.JPG

Please view the above as a half-baked suggestion rather than a fully baked hypothesis

Bill Harris, I like your explanation of 'tektites' for at least some of the pebble-like fragments we have seen amongst the desert pavement. I'm not sure if that's a cut and dried explanation without more data, but it stands to reason that there must be 'tektites' present on Mars somewhere.

Posted by: CosmicRocker Sep 10 2006, 06:31 AM

I've gone over all of the recent MIs and I can't find anything I'd call a tektite. If someone would post a picture identifying one of the suspected critters, I'd appreciate it.

Regarding that berry with the central hole, it's not the first one we've seen on this long trek. That one seems to be one of the occasional concretions that we've come across that has been cleaved in half and abraded. I would interpret the hole as the place where the concretion's center was more friable, so the material was easily eroded away. That is not an uncommon phenomenon in earthbound concretions. The one with the dimple might be the same thing as the first.

The third hole identified is in a clast (fragment) that doesn't resemble a concretion at all. There seems to be several sub-populations of fragments of different origins on the surface here. Among those that are not obviously concretions, some have noticeable porosity. But I must admit that the MI posted by SacramentoBob showing three different, tiny clasts with neat round holes is intriguing. ...just thinking out loud here... I wish I could tie them all together with a pretty pretty pink ribbon, but I can't.

Posted by: Aldebaran Sep 10 2006, 06:54 AM

I've also noticed a disproportionate number of concretions that have split in half.

If we accept that the concretions formed within the evaporite matrix as per the terrestrial analogy, I'd expect to find fine planar inclusions of evaporite within the concretion itself. We've discussed the possibility of changes in hydration states with diurnal temperature fluctuations. Intuitively, any such inclusions would tend to undergo a net increase in volume with an increase in hydration state and this would act as a wedge, exerting internal pressure on the 'berry' causing it to split in the plane of the original strata.

Do you think that's a credible mechanism?

Posted by: Bill Harris Sep 10 2006, 11:49 AM

"Tektites" or "impact lapilli" are the best name I can come up with. Unlike earthly tekties they are neither appear glassy nor aerodynamic (for the most part) and unlike earthly lapilli they are't volcanic. They are the basaltic basal unit melted by the impact, assuming a near-spherical shape in the thin atmosphere and falling onto the ejecta blanket. I think the observation of the larger-sized spherules in this locale is important. Look at the L257's taken at this stop, the larger spherules tend to have a color similar to the basaltic cobbles, while the smaller spherules have a slightly different color. I see we have new Pancams of this crater and the distinctive light-toned rocks, so perhaps this will not be a drive-by sighting. Although we'd like to get to the photo-ops at Victoria, we need to do some science at this stop. Understanding erosional-depositional processes on Mars is the key to understanding the geomorph.

I agree with the idea that the holes in the berries are related to the stalks we've seen. And I wonder if some of the berries are not hollow or have a "softer" internal composition (related to Aldebaran's "planar inclusions"). I'm thinking that we see more broken berries here because of the impact. When the evaporite was catastrophically fractured and pulverized by the impact some of the berries were broken along the fracture lines, whereas with slower weathering processes the evaporite matrix breaks around the berries.

By way of earthly analogy, take a look at the attached...

--Bill

Posted by: Bill Harris Sep 10 2006, 01:16 PM

Here are the latest color Pancams from the current stop, maybe these are next targets. Interesting rocks, we'll discuss later. I need to go fly...

--Bill

Posted by: dvandorn Sep 11 2006, 01:45 AM

I don't know if I'd call them tektites, exactly, but I think the larger rounded bodies in these soils, which tend to have randrop or conical shapes, might well be droplets of impact melt. That would make them similar to tektites in origin and general configuration. But tektites are often formed in the initial blast, from materials near the surface, and are blown a considerable distance away from the impact site. These droplets, if they're impact melt, came from less than 200 meters away. So they were formed later in the impact process (and hence probably contain materials from deeper within the excavation), and were ejected far less energetically than the more far-flung ejecta.

-the other Doug

Posted by: CosmicRocker Sep 11 2006, 04:36 AM

Doug: I don't have a problem with the term tektite. I've always assumed that any impact melt droplet that solidified into a glassy sphere or aerodynamically altered shape was essentially a tektite. I see a lot of spheres and a fair number of multiple sphere agglomerations, but I don't see anything that looks glassy, nor anything that looks aerodynamic. I can discount the importance of the things being glassy by assuming they have had time to devitrify or be recrystalized by some later alteration process, but I really don't see anything that can't be more simply explained by assuming that these spheres are simply the same concretions we have been seeing since day 1.

I think I have seen a very few that could be roughly described as conical, but those looked more like multiply-connected berries that were broken or eroded, or berries that were broken from eroded stalks of the evaporite cemented sandstone, like those we saw at Fram. I'd love to see something new, like evidence of an impact melt, but I am not convinced, yet.

Posted by: CosmicRocker Sep 11 2006, 06:00 AM

I agree with the idea that the holes in the berries are related to the stalks we've seen. And I wonder if some of the berries are not hollow or have a "softer" internal composition (related to Aldebaran's "planar inclusions"). I'm thinking that we see more broken berries here because of the impact. When the evaporite was catastrophically fractured and pulverized by the impact some of the berries were broken along the fracture lines, whereas with slower weathering processes the evaporite matrix breaks around the berries.

By way of earthly analogy, take a look at the attached...

--Bill

Correct me if I am wrong, but the last thing we heard from SS regarding the cobbles was this August 2005 quote: "Oh, yeah, and the cobble we looked at with Opportunity isn't a meteorite, it's a martian rock... and one that's very different from anything we've ever seen before. Busy times... "

I've been wondering about the "basal basaltic unit" too. In this part of Meridiani we are supposed to be sitting on top of several hundred meters of "light colored sediment." Victoria surely didn't excavate basalt, unless there is a surprise inside, or unless the impactor was a secondary of external origin.

Posted by: Bill Harris Sep 11 2006, 10:34 AM

OK, then explain what we're seeing on the ejecta blanket. There have been several substantial or suble differences in the surface compared to the Meridiani plains. Your shot.

The "dark basaltic basal unit" is the holy grail tying the "oh yeah" cobbles to anything. It may not exist, but OTOH, since we have seen only a few meters of several hundred meters of "light colored sediment", we can't say that it doesn't. Your shot at the explanation...

--Bill

Posted by: Gray Sep 11 2006, 02:00 PM

I think Bill might be on the right track. Look again at Nirgal's colorized image of the pebbles:

http://mitglied.lycos.de/user73289/misc/oppy_m924pan_col_d.jpg

Many of the larger grains have a shape that looks like a Hershey's kiss. Some have suggested that they might be ventifacts. But it would take winds blowing equally from every direction to sculpt a grain that way. Unlikely IMO. Bill's suggestion that they may be formed by a melt/impact process makes more sense to me at this point.

One of the grains at the lower left-hand edge of Nirgal's image provides some tantalizing evidence for this idea. The grain is cut by the edge of the image, but you can see that there is a smaller grain (blueberry) contained it a larger grain. It looks as if part of the larger grain has wrapped around the smaller grain.

I'm envisioning a process like this: the meteor strikes the surface of Mars and in the process melts many of the silicate minerals in the crust (it could be a lower basalt or the basalt sands). Molten blobs fly through the air assuming a streamlined, rain-drop shape. The strike the surface while still partly molten. This flattens the bottom but they still retain a streamlined shape in the upper part.

If the grains fell, while partly molten on a surface which was already littered with the smaller blueberries. (A process Bill has already proposed). The under side of the "Hershey's kiss" grain would have the smaller blueberry imbedded in it. That partial view of a grain with the embedded blueberry might be evidence for this.

- gray

Posted by: dvandorn Sep 11 2006, 03:30 PM

http://mitglied.lycos.de/user73289/misc/oppy_m924pan_col_d.jpg

Yep. Please note that in the attached image, there are really four different size populations in the objects we see.

The finest particles are dust-sized, and are consistent with windblown dust particles or the aeolian erosional remnants of local larger bodies which have been worn down by local winds. These particles form the primary portion of the soil matrix at this site, and they resemble (a lot) the fine dust portion of the soil that we've been seeing all along.

The next largest size of body resemble, in size and general shape, the blueberries we've seen ever since Eagle. They seem to be more broken up -- some appear to have started out spherical but have been partially or completely shattered. But these look like the blueberries we've been seeing.

The next largest size of body we see are what Bill is calling tektitic. Most of them seem to have a conical shape, and while the linked image doesn't show this well, many of them have a small depression, pit or hole at the apex of the cone. One would be tempted to say, with a quick glance at the image, "Oh, yeah, those are blueberries." But if you compare their size (larger than the blueberries we've seen before) and their presence in the same soil with smaller bodies that far more closely resemble the blueberries we've seen before, you can see that these are different types of bodies. The conical (or teardrop) shapes seem unlikely to be ventifacts because of the very small size of the bodies and because they appear to have been evenly shaped into regular cones all along their circumference.

There is one larger sized body type in this image, as well -- a more rough-edged pebbly kind of stone that someone remarked (sorry, I don't remember who originally noted this) looks rather like chert or flint. These have multiple fracture planes that form their surfaces, and are significantly larger than either the blueberries or the tektitic droplets.

These four different types of bodies seem to be fairly well mixed in the soil here. But they are definitely all different in appearance, and I would imagine they are all different morphologically.

I'm about 80% convinced that the conical or teardrop shaped objects are some form of impact melt. I don't necessarily have an explanation for why they don't look glassy. I suspect it's a matter of either their initial composition or, more specifically, the volatiles content of the original melt that is responsible for this appearance.

-the other Doug

Posted by: CosmicRocker Sep 12 2006, 05:28 AM

Thanks Gray and dvandorn for the image and the descriptions. I'm sorry it took me so long to catch on. At least now I know what you guys are talking about. When I first saw those MI's I thought it was curious that so many of the spherules seemed to have a dimple on the very top. It seemed odd to me that all of those spherules would be oriented in the same direction, but they do appear to have the approximate shape of a "Hershey's chocolate kiss" candy. That was a good analogy to use to describe the appearance for me.

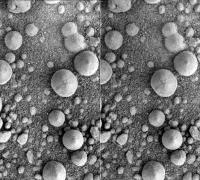

After I understood that, I couldn't help but wonder why we didn't see at least a few of these things tipped over to better reveal that shape. I went back to the original MIs and noticed that several of them captured overlapping areas, thus providing some pretty nice stereoscopic image pairs of at least some of them. I made an anaglyph of the best pair I found, put it next to a similar MI anaglyph NASA/JPL created of some berries at Eagle crater for comparison. I know some of you prefer the side-by-side stereopairs, so I will try to post them as well, or in a following message if they both cannot fit below the forum limit. I think the second is a parallel image pair, so you may need to reverse them if you prefer to view them in crosseyed mode. I am using the excellent program StereoPhotoMaker that was recommended by another member here, and I think I haven't yet learned to force it to make a crossseyed pair.

I think these things we are seeing here appear pretty spherical in 3D, and quite similar to those we saw in Eagle crater. I'd like to hear what other people think, to make sure I am not deceiving myself.

Posted by: Bill Harris Sep 12 2006, 11:15 AM

That is what is puzzling about the larger "Hershey's Kiss" spherules. They seem to be oriented in mostly the same direction (point up) and from the very subtle shadows I have the impression they are faceted (ie, quasi-pyramidal more than conical). Therefore, I was initially thinking wind-created venifacts formed in-place instead of tectite-oid features falling and orienting by chance.

I dunno, let me look closer at the "faceted" issue. And after all, we are looking at a sample of a few spherules out of millions. And I'd like to get MB reading to see which spherules are basaltic and which are hematitic.

Any ideas about the rocks exposed in Emma Dean? I keep hoping for a closer look...

--Bill

Posted by: Floyd Sep 12 2006, 12:05 PM

If the "Hershey's Kiss" spherules are all pointing up, wouldn't that imply that the soil has never been mixed? Their shape is not so Hershey's Kiss like that they would sort to sit on their bottoms?

Posted by: RobertEB Sep 12 2006, 12:27 PM

Perhaps they are blueberries that have been sitting on the surface so long, wind has eroded their ‘tops’ into that shape.

Posted by: Indian3000 Sep 12 2006, 05:02 PM

CAHVOR color projection L257

R = 80% L2 + 20% L7

G = 100% L5

B = 80% L7

Posted by: Ant103 Sep 12 2006, 07:21 PM

Wow! Delicious colors on the first pic Indian3000, I love it. ![]()

Posted by: Ant103 Sep 13 2006, 04:37 PM

I made a crossed-eyes (or parallel ![]() what is the difference between this two?) animation from Sol 917 navcan pictures.

what is the difference between this two?) animation from Sol 917 navcan pictures.

Posted by: Gray Sep 13 2006, 04:44 PM

Cosmic

Good job on the anaglyphs of the pebbles. You're right, they do look more spherical thanI had originally thought. Now I'm scratching my head again. I still think the "impact tektite" explanation might work, but it's very conjectural.

Indian - good looking colors!

Posted by: CosmicRocker Sep 13 2006, 07:02 PM

Indian3000: That is very nice color, and thanks for giving us your "recipe."

Ant103: A parallel stereo pair is one in which the image for the left eye is on the left, and the image for the right eye is on the right...so your eyes are looking in parallel directions when viewing it. A cross-eyed pair is the the opposite, where the left image is on the right and the right image is on the left...so your eyes must be crossed to view the stereo pair.

Gray: Thanks. I am very curious about the ejecta. If they really are going to spend some quality time at Emma Dean, perhaps we'll see it and it's relationship to the soil below the wheels. Like Bill, I too am hoping for a closer look. It would be an anxious wait for us all, but I'm sure it will make it easier to understand what we see when finally at Victoria's rim.

Posted by: Bill Harris Sep 15 2006, 04:57 AM

Here is an L257 Pancam of what I suppose to be the next IDD target, Cape Faraday. Note the blueberries imbedded in the rock along bedding planes. They are of the "large-size population" and dispell the notion that the large spherules are impact lapilli. They represent a new member of the size and morphological distribution of the hematite concretions. I suspect that these larger blueberries are from a lower horizon of the evaporite unit unheretofore exposed, and which was brought to the surface by the Victoria impact.

I'm looking forward to setting our CCDs on the reddish and purple-tinged and rough-textured rocks we see in Emma Dean. Victoria will still be there in a few Sols...

--Bill

Posted by: CryptoEngineer Sep 15 2006, 06:25 PM

JPL just released http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/jpeg/PIA08737.jpg of a 30km crater on Titan.

The apron of ejecta surrounding it immediately reminded me of Victoria.

Perhaps these sharp-edged blankets are a common feature of craters

forming in saturated soils, within an atmosphere. (Of course, the

fluid on Titan is a hydrocarbon mix, and the atmosphere mostly

nitrogen).

Full post http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA08737.

Posted by: Marcel Sep 15 2006, 06:51 PM

Seems to me the closer we get to craters, the " berrieer" (more and more spherical) it gets.

Could craters and berries be related ?

Posted by: Pavel Sep 15 2006, 09:02 PM

Could craters and berries be related ?

Apparently, the crater ejecta is eroded exposing the berries. The ejecta is fractured by the impact and thus easier to erode. Also, the dust is blown back to the crater, exposing the surface to the faster dust particles during the storms until there are enough berries on top of the rocks to protect them from further erosion.

Posted by: volcanopele Sep 15 2006, 09:29 PM

forming in saturated soils, within an atmosphere. (Of course, the

fluid on Titan is a hydrocarbon mix, and the atmosphere mostly

nitrogen).

Posted by: Bill Harris Sep 17 2006, 12:43 AM

Here is an MI of part of the Cape Faraday rock from Sol 939. An interesting texture has been eroded onto the rock, which shows the evaporite in vertical cross-section and not the usual bedding plane section. I may be wrong, but there seems to be the light-toned evaporite dust adhering to one side of the blueberries. I don't know if this is on the downwind side of the spherules or has accumulated on the upwind. I'm not sure of the rover orientation (I think that the target rock is to the NE of Emma Dean), and the MI image is presented un-inverted so that it matches the Pancam planning image.

--Bill

Posted by: dvandorn Sep 17 2006, 06:16 AM

The "Hershey's kiss" berries in this MI view are not only conical, the cones are slightly faceted. However, I still have a hard time believing that this is due to aeolian erosion.

My main objection to this being aeolian erosion is that, if these kisses are hematitic concretions that have been eroded out of evaporite from Victoria ejecta, they ought to have been emplaced on the surface (and thus exposed to winds) *after* some, if not most, of the blueberries out on the plains. All other things being equal, the berries on the plains, having been exposed to winds for a longer period of time, ought to display a greater degree of erosional faceting.

They don't. In fact, the blueberries seen in the soils out on the plains (and in both Eagle and Endurance, for that matter) were remarkably spherical. I don't remember seeing a single concretion, up until this last series of MIs in the Victoria ejecta, which displayed obvious ventifact forms. These are the very first examples of this type of morphology in the blueberries (if that's what they are) that I can recall.

Of course, the key to the above statement is "all other things being equal." If these are acutally hematitic concretions, they would seem to have eroded out of Victoria ejecta made up of concretion-bearing evaporite, correct? But evaporite emplaced this close to the rim of a crater this big must have been awfully shocked. What do berries which erode out of *highly shocked* evaporite look like? Maybe they look like Hershey's kisses...

One thing bothers me, though. We're only 120 meters away from the rim of a crater that was created in an enormous translation of kinetic energy into thermal energy. It was big enough to dig a crater that was, originally, probably at least a half a kilometer wide and several hundred meters deep.

I have a hard time imagining how the ejecta emplaced only a couple of hundred meters, at most, away from the edge of the hole made by this powerful explosion could have been so relatively unaltered that it would look even remotely like the evaporite we saw out on the plains. If, in fact, these berries are hematitic concretions which formed exactly the same way those out on the plains formed, and if they were originally formed in the target rock into which the Victoria impactor struck, why have so many of them survived seemingly intact (if mysteriously eroded into little cones)?

And if the "kisses" are the same size as the concretions we saw out on the plains, then what are the mostly spherical bodies which, except for size, closely resemble the mostly-spherical plains berries? Are these also concretions? If so, why are they fairly uniform in size but only a fraction the size of the plains concretions? And if the kisses and smaller, rounder bodies are both concretions, why do they both exist? We're not seeing spectrum of sizes, here, that would suggest the result of erosional or shock processes -- we're seeing a small population of kisses, and much larger population of fairly uniformly-sized smaller, rounded bodies. Such a neat division of populations suggests differences not in erosional processes, but in formative processes. And in composition. In other words, I think it makes more sense to assume that the kisses and the small spheres have different compositions and/or formation histories.

Ah, but if only one of these two populations is made up of hematitic concretions, which one is it? Perhaps there is a clue in this most recent MI image -- there is a feature in the dust "above" the rock face that looks rather like a worm. But this 'worm' is exactly the same size, in planform, as the small spheres. It resembles the small spheres in almost all respects, except that it is a drawn-out blob instead of a spherical blob.

Perhaps this would suggest that it is the small spheres that were once molten? I can visualize a spray of impact melt droplets solidifying into spheres in the very thin air as they flew out of the crater (not enough air pressure to compress them into teardrop shapes), and that while most of them fell as individual, rounded drops, some of them would hit each other in mid-air and form into, among other forms, chains of drops that ended up looking like tiny little worm-forms.

In other words, could the small spheres be the impact melt we've been looking for?

One last thing -- this all assumes that the annulus we see around Victoria is primarily the erosional remnants of her ejecta blanket. However, if Victoria is indeed a once-covered-over crater that has been (or is being) exhumed, then the soil we're looking at maybe doesn't incorporate much at all from the original ejecta. Maybe we're just looking at the erosional remnants of the materials that covered Victoria, and its actual ejecta blanket is still buried and inaccessible to our eyes? Of course, if that's the case, you would expect these soils to look exactly like any other patch of blueberry-paving in Meridiani, and it most definitely looks different from the plains soils. So I tend to discard the once-buried-now-exhumed crater theory. (Besides, it looks like a sharp, fresh crater -- most of the exhumed craters I've seen on Mars look far older and more eroded than this.)

Well, that's my two cents worth, anyway... ![]()

-the other Doug

Posted by: Pando Sep 17 2006, 06:42 AM

In other words, could the small spheres be the impact melt we've been looking for?

Interesting, but there is one piece of evidence that shoots this down. The perfectly spherical hematite spherules were found embedded between various layers of bedrock at Eagle and Endurance. This can't be explained by impact melt since the spherules were still in their original strata.

Posted by: Bill Harris Sep 17 2006, 09:07 AM

This ejecta apron, and the blueberries in general, are quite a conundrum, no?

Even though there was a tremendous amount of energy transferred to the bedrock by the impactor and most of the bedrock was pulverized there were undoubtedly "quiet" nodes of lower energy where the shock wave cancelled itself out. This is a classic problem in designing a shot to fracture rock in mining. Therefore you will find pieces of less-fragmented bedrock. And an impact crater like Emma Dean can bring these fragments to the surface.

The hershey's kisses are a mystery. I have problems with the venifact (aeolian erosion) idea but it does offer a good explanation of observation that the facets have a similar orientation, as do the kisses with the point=up. Spherules emplaced by the impact would be random.

We saw blueberries embedded in bedding surfaces at Eagle and Endurance and a couple of examples of this in the Cape Faraday rock.

I saw the "w"-object and wanted to see stereo pairs before mentioning it. Too, too odd. ![]()

This stop may be a delay in reaching the photo-op at Victoria but there is good science to be gained here.

--Bill

Posted by: Oersted Sep 17 2006, 10:23 AM

-the other Doug

You don't mean that re: the depth, do you?

Posted by: Nirgal Sep 17 2006, 12:14 PM

Very good job on the colorization from the uncalibrated stretched JPGs !

It almost looks like if it was one of the PDS-calibrated "true" color images

Also thanks for providing the formula (I'm surprised that a simple linear combination of the

filter channels already yields such "near-calibrated-looking" results since I once experimented with more complicated non-linear color mappings but with poorer results ...

Posted by: dvandorn Sep 17 2006, 04:42 PM

Actually, I was suggesting that the smaller spherical objects we're seeing here in the annulus are *not* hematitic concretions, and thus are entirely different in morphology and composition from the blueberries we saw in Eagle, in Endurance and on the plains. In this hypothesis, of what we are seeing here in the soils of the annulus, only the bodies that have been modified into conical shapes would be concretions. The smaller spherical bodies, while they resemble mini-concretions, would be (I'm suggesting) impact melt droplets.

-the other Doug

Posted by: CosmicRocker Sep 18 2006, 05:01 AM

I can see how some of the berries appear Hershey's kiss shaped, due to the brighter spot at top dead center, but I don't think they really are that shape. If the 3D images I posted were not convincing, then take a look at the shadows these things cast. The shadows should display a projection of the conical shape, if that is their true shape. Instead, the shadows display circular or eliptical shapes.

Look above to the false color pancam from sol 936 that Bill posted in message #92. It shows a good sampling of the spheroids in a wide range of sizes, and they all seem to be casting rounded shadows. They are all the same color and hue, suggesting that they are similar in composition, so it is hard for me to believe there is a sub-population of impact melt spheroids, even though I'd like to see some of those. I'm just not sure if much melt would even be created by an impact into rocks of this composition.

Looking at Emma Dean crater, we finally see just what one would expect if it was a hole punched into the ejecta blanket of Victoria...a jumble of lithologies, and nothing like Beagle and earlier craters. I am eager to move on to Victoria, as the rest of you are, but I really hope they move closer to this hole and take a closer look at it's walls. I'd really like to take a close look at a cross section through the ejecta. I'd also like to know if that is a piece of the Halfpipe formation right of center on the opposite side of Emma Dean. This is a pretty nice little crater. I wonder if Oppy will wander into it.

Posted by: dvandorn Sep 18 2006, 05:30 AM

This comment reminds me very much of an exchange between Dave Scott, on the Moon, and Joe Allen, the CapCom back in Houston. It occurred just a few minutes after Scott and Irwin had discovered the "Genesis Rock," a piece of nearly pure plagioclase, at the rim of a small crater on the Appenine Front. Despite the excitement of the find, Allen was pressing the crew to move on to their next stop:

Scott: Hey, Joe, this crater is a gold mine!

Allen: And there might be diamonds in the next one, Dave.

So, yes -- Emma Dean may have some very good finds in it. But, as always, we have to remember that Victoria might have diamonds in it...

-the other Doug

Posted by: Bill Harris Sep 18 2006, 09:04 AM

The hershey's kisses aren't shaped exactly like our chocolate confection, the departure from spherical is very small. Physical and color differences are very subtle, but nonetheless present.

Unlike the carbon-based rovers in Apollo, the silicon-based rovers in MER are not on a tight time schedule for the traverse since they will run out of oxygen at a known point in time. Although unlike the Black Knight they are not invincible, the rovers are far from loonies. We ought to keep moving on because the clock is ticking but not at the cost of science. The diamonds at Victoria will be there in a few Sols more. Science as well as photo-ops.

--Bill

Posted by: CosmicRocker Sep 19 2006, 05:42 AM

This is a bit off topic, but since this thread seems to have the attention of some of the geologizers, I hope it will be appreciated. I came across an abstract from last Spring's LPSC that I had somehow missed. http://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2006/pdf/2312.pdf

This 2 page pdf should not be too large of a download for those on dialup, and it addresses several Meridiani observations that have resulted in many long-winded discussions here about things like ripples, cobbles, polygons, and mini-craters. I'd recommend this short paper to anyone interested in those topics. Anatolia is seen as a large scale version of volume-loss polygons observed on many scales. Mini-craters are viewed as either small craters or rimless pits...and more elongated sapping features are described as pit chains. I like the way this abstract condensed a huge amount of observations and interpretations into only 2 pages. There are a few more diamonds to be found in it. ![]()

Posted by: Bill Harris Sep 19 2006, 11:08 AM

It is almost an epiphany to read something that mirrors observations that you have had for a long time. I really need to spend more time reviewing the current literature. The previous post is in no way OT.

BTW, there is discussion about the ejecta apron and the Emma Dean roadcut in Squyres' current Mission Update at http://athena.cornell.edu/news/mubss/ .

--Bill

Posted by: Bill Harris Sep 20 2006, 08:50 AM

And mixed in with the initial Navcam views of Victoria's stratigraphy we have a couple of partial-frame Pancam sequences of selected Emma Dean features. L257's here, with interesting compositional changes.

--Bill

Posted by: Stu Sep 20 2006, 09:59 AM

Yep, I noticed those too Bill... very interesting... I posted this over on another thread but I think it slipped past everyone...

And the one you pointed out...

Powered by Invision Power Board (http://www.invisionboard.com)

© Invision Power Services (http://www.invisionpower.com)