Printable Version of Topic

Click here to view this topic in its original format

Unmanned Spaceflight.com _ Messenger _ MESSENGER News Thread

Posted by: paxdan Apr 20 2005, 11:22 AM

http://www.nasa.gov/centers/kennedy/news/releases/2004/59-04.html on August 3rd 2004, http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/messenger/main/index.html will become the first spacecraft to orbit http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mercury_(planet).

News and updates are availbale via Johns Hopkins University MESSENGER http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/index.html and the Kennedy Space Center's MESSENGER http://www.ksc.nasa.gov/elvnew/messenger/index.htm.

There will be an earth flyby in August followed by a couple of swings by Venus and three velocity scrubbing passages past mecury before the craft enters orbit in March 2011.

April 18, 2005 http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/status_report_04_18_05.html from JHU. Extensive JHU FAQs page http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/faq/index.html.

Posted by: Buck Galaxy May 29 2005, 06:19 PM

News and updates are availbale via Johns Hopkins University MESSENGER http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/index.html and the Kennedy Space Center's MESSENGER http://www.ksc.nasa.gov/elvnew/messenger/index.htm.

There will be an earth flyby in August followed by a couple of swings by Venus and three velocity scrubbing passages past mecury before the craft enters orbit in March 2011.

April 18, 2005 http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/status_report_04_18_05.html from JHU. Extensive JHU FAQs page http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/faq/index.html.

I for one can barely wait for Messenger. There is a big section of Mercury we've never seen, and I would love to also see close ups of the huge polar ice deposits.

Posted by: Jeff7 May 29 2005, 08:14 PM

News and updates are availbale via Johns Hopkins University MESSENGER http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/index.html and the Kennedy Space Center's MESSENGER http://www.ksc.nasa.gov/elvnew/messenger/index.htm.

There will be an earth flyby in August followed by a couple of swings by Venus and three velocity scrubbing passages past mecury before the craft enters orbit in March 2011.

April 18, 2005 http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/status_report_04_18_05.html from JHU. Extensive JHU FAQs page http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/faq/index.html.

I for one can barely wait for Messenger. There is a big section of Mercury we've never seen, and I would love to also see close ups of the huge polar ice deposits.

"Big section" is putting it mildly.

Ugh, searching for Mercury Mariner on Google turns up more matches for some damn new SUV called just that. Of course, it is a hyrbid with mileage about equal to my car, so I guess I can't really complain.

Why is it such a long time until Messenger gets to Mercury?

Oh, seems NASA anticipated this question. http://www.nasa.gov/missions/solarsystem/f_messgrav.html. Orbital insertion around something so small requires a slower speed than, say, something like Cassini.

Should definitely be an interesting mission though. That's a fascinating probe too - all the adaptations needed for flying so close to the sun.

Posted by: tedstryk May 29 2005, 08:33 PM

Mariner 10 Photographed 45% of Mercury, or almost half. But only basically one illumination condition was covered - due to orbital mechanics, the same side was illuminated on all three flybys. And the views of many areas were very forshortened on the limb.

Posted by: MiniTES May 29 2005, 09:51 PM

MESSENGER = strained acronym. It's even worse than Hipparcos.

Posted by: JRehling May 31 2005, 01:27 AM

As others noted, Mariner 10 imaged about 45% of the surface, not all well. Radar has provided some nice additional coverage, not all of which is available publicly.

But we're not going to see the polar ice deposits, at least not in visible wavelengths. They are, if they exist at all, in areas of permanent shade. It wouldn't take much sunlight at 0.4 AU to melt (vaporize) ice.

I suppose it's possible that a crater floor could be imaged in light reflected off of the crater wall, if imaging conditions are just right, and if that kind of lighting isn't enough to make any such parcel of ice disappear.

Posted by: tedstryk May 31 2005, 02:12 AM

But we're not going to see the polar ice deposits, at least not in visible wavelengths. They are, if they exist at all, in areas of permanent shade. It wouldn't take much sunlight at 0.4 AU to melt (vaporize) ice.

I suppose it's possible that a crater floor could be imaged in light reflected off of the crater wall, if imaging conditions are just right, and if that kind of lighting isn't enough to make any such parcel of ice disappear.

I doubt there is reflected light weak enough to not melt ice over eons and bright enough for Messenger to use it to create an image, especially with the glare from whatever is reflecting the light.

Posted by: edstrick May 31 2005, 05:02 AM

Uh... doesn't Messenger have a laser altimiter?... that measures reflectance, as well as delay-time which equals range...

I'd have to check, but I thought it did...

Posted by: Bob Shaw May 31 2005, 11:19 AM

I'm reminded of the darkside images taken of the Moon by Clementine - I wonder how well Venus will illuminate the shadowed parts of Mercury (obviously, at the right time of the Mercurian year it'll be *much* brighter).

Posted by: JRehling May 31 2005, 03:43 PM

A full Venus has an absolute magnitude about 4 times that of the Earth, but is 130 times farther from Mercury than Earth is from the Moon. Venusshine onto Mercury should thus be about 1/4200 of the effect of earthshine on the Moon. Depending upon the specs of a camera, that could be used for some imaging, although I suspect that the Messenger camera would not be built for light-sensitivity the way, say, New Horizon's are. The kicker: if the polar areas never see the Sun due to the geometry, they'll never see Venus either.

Posted by: JRehling May 31 2005, 03:52 PM

I'd have to check, but I thought it did...

Yes, the polar ice (if it exists as such) should be detectible through several instruments, and the laser altimeter is one possibility. If they are they, we will end up with image products, I'm sure, mapping them. But we won't have traditional imagery as such (I realize the distinction can be gray -- at what extent does a collection of reflectance data equal an image??).

I'll add that we don't have proof yet that the shadows of the polar craters hold full-fledged surface ice deposits -- only that the areas are highly reflective in radar. They may be dust-covered ice that appear as normal regolith in vis/IR. Whatever is going on there may possibly not involve water ice, but sulfur, for example. Verifying the suspected ice and determining whether or not any such ice is on the surface is something to find out. Finally, the same investigation will be happening with regard to the (presumably similar) phenomenon at the lunar poles. I guess LRO will shed light on the lunar version before Messenger gets to Mercury. (It's quite a coincidence that of the two large airless worlds in the inner solar system, both have large areas of permanent shadow near their poles! -- this wouldn't be true of the Earth or Mars.)

Posted by: Bob Shaw May 31 2005, 04:04 PM

Darn - I hadn't thought of that, and it's probably pretty obvious! Not only will libration effects be pretty minimal (unlike the Earth-Moon situation, where something interesting might be a goer), but as Venus and Mercury are probably in all sorts of orbital resonances there's likely to be only a few chances to view the same areas, badly illuminated at best. Oh, well, back to the drawing board.

OK, what about the Zodiacal Light...

Reflections from Comets...

Starlight...

Posted by: Chmee May 31 2005, 04:53 PM

Or how about a high-yield fusion bomb detonated in orbit? Use it like a giant flash-bulb to take a picture!

You could even use the x-rays generated by the explosion to look for hydrogen.

Posted by: RNeuhaus Jun 1 2005, 02:48 AM

Is Mercury atmosphere similar to Moon rather than Mars? What are the composition of Mercury's atmosphere (helllium, hydrogen, oxigen, potassium and sodium)? Wiill the Messengare space answer these questions?

Posted by: paxdan Jun 1 2005, 08:39 AM

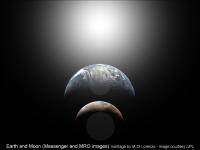

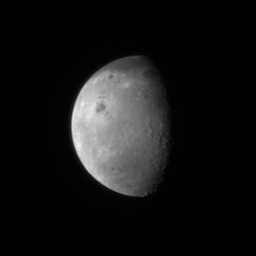

Earth from MESSENGER at 29.6 million km

Posted by: Sunspot Jun 1 2005, 08:40 AM

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/press_release_5_31_05.html

"NASA’s Mercury-bound MESSENGER spacecraft – less than three months from an Earth flyby that will slingshot it toward the inner solar system – successfully tested its main camera by snapping distant approach shots of Earth and the Moon."

Posted by: um3k Jun 1 2005, 05:01 PM

No focusing problems on this baby! ![]()

Posted by: lyford Jun 1 2005, 06:30 PM

I always enjoy these far off shots of Earth. They really drive home how BIG space is and how SMALL our home is...

Anybody seen a higher rez version?

Posted by: paxdan Jun 1 2005, 07:43 PM

Anybody seen a higher rez version?

i think this is the highest we are going to get without image processing.

from the article:

The image is cropped from the full MDIS image size of 1024x1024 pixels

Posted by: BruceMoomaw Jun 1 2005, 07:49 PM

It will indeed provide a great deal of additional information on Mercury's atmosphere -- which is incredibly rarified and thus similar to the Moon's atmosphere rather than Mars'. Indeed, both worlds actually have what is described as an "exosphere" -- from which the atoms and molecules escape almost immediately -- rather thann any stable atmosphere. Its surface density is only about one trillion atoms per cubic centimeter. (I'd have to look this up -- I haven't been following the discoveries regarding Mercury's atmosphere closely -- but I think this is an atmospheric density roughly a trillionth of Earth's.)

We also have confirmed recently that Mercury's exosphere contains small amounts of calcium. The exosphere seems to come from atoms "sputtered" off Mercury's surface rocks by the impacting atoms of the solar wind -- a phenomenon much more intense on Mercury than on the Moon, thanks to its closer proximity to the Sun -- and it is suspected that Mercury's magnetic field focuses this activity so that much of the sputtering occurs near the planet's poles.

Messenger's "Mercury Atmospheric and Surface Composition Spectrometer" really consists of two separate, entirely different instruments that might as well count as two separate experiments; they have little to do with each other. Its near-infrared spectrometer will map surface mineral composition, while its ultraviolet spectrometer will specialize in measuring the density, distribution and composition of the exosphere. (I don't know whether it can measure calcium, but I suspect it can -- and one of its goals will be to try to identify additional elements in the atmosphere, such as magnesium, silicon and sulfur.) Messenger's "Energetic Particle and Plasma Spectrometer" also has some ability to directly detect different elements' ions by mass spectrometry -- again, I'd have to do some digging for the details.

Posted by: Bob Shaw Jun 2 2005, 09:00 PM

Bruce:

Can Messenger's instruments detect He on the surface of Mercury? I'm thinking of those old lunar He3 strip-mining plans...

Bob Shaw

Posted by: JRehling Jun 3 2005, 12:53 PM

Can Messenger's instruments detect He on the surface of Mercury? I'm thinking of those old lunar He3 strip-mining plans...

Bob Shaw

In principle, He can be detected (quite easily, in fact), but that would only be if it existed in bulk concentrations, which it certainly will not. Lunar Prospector showed no He signal I'm aware of on the Moon. The quantity just isn't much to speak of.

Posted by: Buck Galaxy Jun 4 2005, 02:46 AM

Huh? I thought the moon's regolith was full of He3?

Posted by: Phil Stooke Jun 4 2005, 03:05 AM

Buck Galaxy said:

Huh? I thought the moon's regolith was full of He3?

No - it has minute amounts of He3. Major strip-mining would be needed to collect the amounts needed for the proposed power schemes.

Phil

Posted by: BruceMoomaw Jun 4 2005, 05:55 AM

Specifically, it's about one part He-3 per 100 million -- which gives you a better idea of the serious problems with mining the Moon for He-3 even if we finally do figure out how to fuse the stuff commercially (which we are absolutely nowhere near right now).

Posted by: Bob Shaw Jun 4 2005, 05:26 PM

Mining the moon for He3 would, of course, give us access to all sorts of other things in the process - not least being meteorites from Earth, Mars, Venus and so on. Possibly even fossils from a certain nearby life-bearing planet (our own!).

Posted by: Toma B Jun 15 2005, 04:41 PM

So there will not be another image of Earth for how long? ![]()

Why don't they snap a picture at least once a week? ![]()

Posted by: BruceMoomaw Jun 16 2005, 02:56 AM

Because Messenger is usually too close to Earth to see it as more than a speck -- only during its close flybys of Earth will its camera be able to see Earth clearly. (I believe there is only one more Earth flyby planned before it moves on to using repeated flybys first of Venus and then of Mercury itself to finally put itself into an orbit almost parallel to Mercury, thus allowing it to use an acceptably small amount of fuel to finally brake into orbit around Mercury itself. The Europa Orbiter -- when they finally fly it -- will, after it enters orbit around Jupiter, use repeated flybys of Callisto, Ganymede, and finally Europa itself to match orbits in a similar way with Europa before braking into orbit around Europa.)

Posted by: BruceMoomaw Jun 16 2005, 02:57 AM

"Because Messenger is usually too close to Earth to see it as more than a speck..."

Gaaah. I'm going senile. Make that "too FAR FROM Earth to see it as more than a speck".

Posted by: gpurcell Jun 16 2005, 03:34 PM

Bruce, do you know if they are planning to do science during the Venus encounters?

Posted by: BruceMoomaw Jun 17 2005, 06:54 AM

Yes indeedy. Quite a bit (even including using Messenger's laser altimeter to map Venusian cloud top altitudes). The question is whether it will do much of note that Venus Express won't (hopefully) already have done.

Posted by: JRehling Jun 28 2005, 12:05 PM

Gaaah. I'm going senile. Make that "too FAR FROM Earth to see it as more than a speck".

Usually, true, but it's getting closer all the time during these few months. The mission site now has animations depicting the Earth/Venus flybys, and I have some hope that Messenger could produce the "definitive" CCD images of Earth from space. There are darn few good CCD images of the full Earth, but Messenger will have an almost-full Earth for most of its approach, when Earth would fill and more than fill its camera frame. If they got some full-color shots at 6-hour intervals, it would be a wonderful thing, and an unusual photo credit for a Mercury-bound craft.

Posted by: djellison Jun 28 2005, 12:27 PM

Galileo and NEAR both did it - producing movies of the flybys by the time they'd finished

Doug

Posted by: Toma B Jun 28 2005, 01:37 PM

They did it....BUT WHERE ARE THE IMAGES OR MOVIES???

There are only few images...here and there.

Posted by: djellison Jun 28 2005, 01:50 PM

ERmmm..

NEAR - http://near.jhuapl.edu/Images/.Anim.html

specifically - http://near.jhuapl.edu/Voyage/img/earth_swby_lg.mpg

Galileo

http://galileo.jpl.nasa.gov/gallery/earthmoon-all.cfm

Took 60 seconds to find them

Doug

Posted by: Bjorn Jonsson Jun 28 2005, 03:24 PM

And if you want thousands of PDS-formatted Galileo images of the Earth there's always this:

http://pds-imaging.jpl.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/Nav/GLL_search.pl

Posted by: JRehling Jun 28 2005, 04:48 PM

The NEAR stuff is of a half-Earth and looks like it was compressed to the point of severe data loss. You can see lone pixels of red standing out with no other red around them. Maybe there's quality data there somewhere?

Galileo's images are nice, but suffer just a bit for being a very gibbous Earth and (like NEAR) highlighting Antarctica, which misses out on the egocentric "There I am!" potential, but also just looks atypical of any other land mass.

What I'm hoping is that Messenger produces a better product. Galileo's are not bad, but fall shy of canon-level (currently, that one overused Apollo image is about the only such image to have a full Earth and an inhabited continent).

Posted by: Sunspot Aug 2 2005, 07:45 PM

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/press_release_8_02_05.html

NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft, headed toward the first study of Mercury from orbit, swung by its home planet today for a gravity assist that propelled it deeper into the inner solar system.

Mission operators at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Md, say MESSENGER’s systems performed flawlessly as the spacecraft swooped around Earth, coming to a closest approach point of about 1,458 miles (2,347 kilometers) over central Mongolia at 3:13 p.m. EDT. The spacecraft used the tug of Earth’s gravity to change its trajectory significantly, bringing its average orbit distance nearly 18 million miles closer to the Sun and sending it toward Venus for another gravity-assist flyby next year.

Posted by: dilo Aug 4 2005, 06:33 AM

waitng for the movie...

The picture reported in the Messenger site, taken with a telescope from Earth, show some darkening in the central part... look to this enhanced version:

Could be due to spacecraft re-orientation?

Posted by: Myran Aug 4 2005, 01:35 PM

Either reorientation or its in a constant slow rotation.

Posted by: djf Aug 28 2005, 02:19 AM

Just noticed this: http://planetary.org/news/2005/messenger_flyby_movie_0826.html

The movie of the rotating Earth receding in the distance is beautiful. It appears the dark, non-reflective area (i.e. dry land) going into darkness between 07:00-09:00UT is the north coast of Australia. Then near the end of the clip the deserts of the Arabian Peninsula and North Africa are visible through the clouds.

Posted by: deglr6328 Aug 28 2005, 02:54 AM

Oh that is just spec-freakin'-tacular! So smooth animation too! Wish there were a higer resolution version though.

Posted by: hendric Aug 28 2005, 01:48 PM

We do have one hell of a beautiful planet. ![]()

Anyone know of rotation movies of other planets?

Posted by: JRehling Aug 28 2005, 04:14 PM

No links here, but a quick list from memory:

Jupiter is probably the most prolific, with both Voyagers and Cassini having done movie-quality sequences. I think Cassini also did an approach sequence on Saturn, but it is not released yet. The data is out there for partial rotation sequences of Titan and Iapteus, but that will never be full from a single pass.

There's a nice partial rotation movie of Io in Jupiter's shadow.

Pioneer Venus has a few frames for Venus, but nothing movielike.

Posted by: tedstryk Aug 28 2005, 05:47 PM

Jupiter is probably the most prolific, with both Voyagers and Cassini having done movie-quality sequences. I think Cassini also did an approach sequence on Saturn, but it is not released yet. The data is out there for partial rotation sequences of Titan and Iapteus, but that will never be full from a single pass.

There's a nice partial rotation movie of Io in Jupiter's shadow.

Pioneer Venus has a few frames for Venus, but nothing movielike.

I imagine one could be made from the Mariner '67 Mars images.

Posted by: hendric Aug 28 2005, 08:59 PM

Hmmm...I wonder if they have done any ridiculously high resolution IMAX movies using full resolution shots of these rotations...

Posted by: djellison Aug 28 2005, 10:17 PM

If and when the Messenger data is on the PDS - I'll work it into a WMVHD movie if appropriate. I've been playing with MER imagery at 720p25 format, and it looks fab ![]()

Doug

Posted by: Stephen Aug 29 2005, 01:42 AM

The MESSENGER team has posted a http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/the_mission/flyby_movie.html composed of 358 images they took during their craft's recent flyby showing the spinning Earth during one complete rotation disappearing into the void.

======

Stephen

Posted by: MizarKey Aug 31 2005, 10:00 PM

That movie is one of the most spectacular things I've ever witness...I love the sun's reflection off the ocean and land masses.

To loosely quote "Pale Blue Dot"..."Everyone who has ever lived or died, been written about...was right there" One fragile planet spinning in dark emptiness.

Eric P / MizarKey

Posted by: BruceMoomaw Aug 31 2005, 10:02 PM

It is; it's a lovely piece of work.

Posted by: dvandorn Sep 1 2005, 07:10 AM

That little movie captures the reality of what science fiction films have been speculatively presenting for more than a half a century.

Seeing the real thing at last, in such high definition realism, is immensely moving for me.

-the other Doug

Posted by: djellison Sep 1 2005, 07:24 AM

Correct me if I'm wrong - but Messenger's imager is a 1024 x 1024 instrument isnt it? - I wonder/hope if they captured that data at full res, or downsampled it to 512 x 512. If they DID do it full res, I promise - hand on heart - to make a full resolution version when the data is released.

Doug

Posted by: tedstryk Sep 11 2005, 12:36 PM

I was looking at the chart below. I noticed that beginning in October of next year, this mission should start getting interesting. Given the quality of the earth imagery, I am really excited about what we might see. I also wonder what if any science will be done at Venus.

Posted by: BruceMoomaw Sep 11 2005, 02:27 PM

Quite a bit -- they even intend to use the laser altimeter to measure Venusian cloud top altitudes.

Posted by: tedstryk Sep 11 2005, 05:43 PM

Thanks Bruce. My anticipation is building. Do you have any other information about Venus plans? I haven't seen much on how the Messenger instrument suit would be used.

Posted by: BruceMoomaw Sep 11 2005, 10:59 PM

Several years ago, Sean Solomon told me a fair amount about it -- but I'm not sure whether that's among the hundreds of stored E-mails that I later lost in an Outlook Express breakdown. I'll check when I get the chance. Suffice it to say that they plan to use virtually every Messenger instrument that CAN be used at Venus.

Posted by: um3k Sep 12 2005, 02:37 PM

Does that mean that we'll finally get some true (enough) color images of Venus? (really excited emoticon goes here!)

Posted by: JRehling Sep 12 2005, 06:21 PM

It's easy to get a true color picture of Venus -- take it from Earth! Getting that with excellent resolution and the fuller phases is another matter, but the true color of Venus isn't exactly an outstanding mystery. Note that the ability to align color channels in digital processing helps enormously with the chromatic edge effects that haunted film photography.

http://www.celestron-nexstar.de/referenzen/bilder/c14_venus_gudensberg.jpg

http://users3.ev1.net/~glennlray/Astro/Venus-20010203c.jpg

http://dvaa.org/Photos/TomBash/VenusPhasesC11.jpg

http://www.kk-system.co.jp/Alpo/kk04/v040511a.jpg

Posted by: um3k Sep 12 2005, 06:51 PM

I know you can get them from Earth, I meant pictures taken by a spacecraft. ![]()

Posted by: JRehling Sep 13 2005, 03:16 PM

You can cover a box in foil and put a radio dish on it, place an amateur astronomer and a Celestron inside, and call it a spacecraft flying within 0.25 AU of Venus.

Posted by: The Messenger Sep 13 2005, 04:01 PM

The only problem with the timeline is that at orbital insertion, I will be as old and onry as Bruce ![]()

Posted by: um3k Sep 13 2005, 04:36 PM

I mean a spacecraft...in space. Within a few thousand km of Venus (or however close Messenger is going to get).

Posted by: odave Sep 13 2005, 04:50 PM

From the http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/faq/faq_journey.html#4:

Since they're planning on imaging at visible wavelengths, and given the care they took to do that awesome movie from the Earth flyby, I'd assume we're going to see some kind of true color image releases...

Posted by: BruceMoomaw Sep 14 2005, 07:36 PM

"The only problem with the timeline is that at orbital insertion, I will be as old and ornery as Bruce."

No you won't. By then, I will be significantly older and much more ornery.

Posted by: dvandorn Sep 14 2005, 07:45 PM

You don't need to be old to be ornery (though it helps). I'd say the orneriest person I ever met was Harlan Ellison, back in the late '70s when he was a rather young man. He was ornerier then than most people get to be in their advanced years...

-the other Doug

Posted by: BruceMoomaw Sep 15 2005, 05:52 AM

Let me add to my reputation for orneriness: if you ever see him again, tell him to get off his damned duff and either publish "The Last Dangerous Visions" or at least release the stories he acquired for it from now-dead authors. The very last stories by Edgar Pangborn and Tom Reamy have now been moldering in a box in his office for three straight decades, and I wouldn't be surprised if there aren't a few more stories there by authors who have since gone to their reward.

Posted by: edstrick Sep 15 2005, 08:09 AM

Harlan Ellison: "The Mouth that Walks like a Man"

Being near Harlan is like the Ancient Chinese Curse: May You Live in Interesting Times.

Some of the LDV stories have been released and published, including a postumous collaboration between Cordwainer Smith and his wife, I believe.

Posted by: Bob Shaw Sep 15 2005, 08:48 PM

Bruce:

Yup. The arrogance of the horrible wee big-head, and his terrible attitude to TLDV's contributors (many of whom are now, as you rightly say, ex-contributors), are beyond belief.

Bob Shaw

Posted by: BruceMoomaw Nov 6 2005, 02:20 AM

As I noted in the "Future Venus Missions" thread below, we now have a very detailed description of the science measurements that Messenger will make during its second Venus flyby in June 2007. (It won't make any during its first one because it's near solar conjunction.)

http://www.lpi.usra.edu/vexag/Nov2005/MESSENGER_VEXAG.pdf

Projected arrival data at Mercury for Bepi Colombo, by the way, is now 2017.

Posted by: Rakhir Nov 14 2005, 11:27 AM

Messenger Status Report :

MESSENGER Team Prepares for December Deep Space Maneuver (DSM-1), when the craft’s large bipropellant thruster will be fired for the first time.

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/status_report_11_11_05.html

Rakhir

Posted by: antoniseb Nov 30 2005, 01:48 PM

I saw that Messenger is currently closer to the Sun than Venus is. This is not unexpected, but I thought it was an interesting milestone.

Posted by: tedstryk Nov 30 2005, 03:19 PM

MESSENGER Team Prepares for December Deep Space Maneuver (DSM-1), when the craft’s large bipropellant thruster will be fired for the first time.

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/status_report_11_11_05.html

Rakhir

I am a bit surprised, since I don't think it will be during the communications blackout, that they aren't taking Magnetometer and Energetic Particle and Plasma Spectrometer data, since that wouldn't require a large amount of bandwith or maneuvering.

Posted by: BruceMoomaw Nov 30 2005, 03:23 PM

This is the very last component of Messenger that hasn't already been tried out. (Andy Dantzler said at the COMPLEX meeting that the craft has had a few software hiccups, but no hardware problems whatsoever so far.)

Posted by: tedstryk Nov 30 2005, 03:52 PM

What is "this" referring to? The instruments I spoke of or some earlier post?

Posted by: JRehling Nov 30 2005, 04:37 PM

The main thruster is apparently "this". It will be fired for the first time in this manuever. If "this"

For no particular timely reason, I will re-voice the angst that it is so long between launch and any interesting science (even a Venus flyby)... If the earlier launch window had been hit, the mission would have been accelerated by *years*. The launch window that was used seems to have been about the worst one possible in terms of cruise duration.

Posted by: tasp Nov 30 2005, 06:02 PM

For no particular timely reason, I will re-voice the angst that it is so long between launch and any interesting science (even a Venus flyby)... If the earlier launch window had been hit, the mission would have been accelerated by *years*. The launch window that was used seems to have been about the worst one possible in terms of cruise duration.

Has anyone looked at return paths from Mercury to earth via Mercury, Venus and earth gravitational assists?

Posted by: JRehling Nov 30 2005, 07:53 PM

It should be roughly symmetrical. You can't make the planets reverse direction, but conceptually...

The big problem is that a trip to Mercury starts with a huge rocket on the surface of the Earth. Getting a big rocket to the surface of Mercury is going to be a problem. The requirement would be at least to reach Mercury escape velocity and then enter a minimum-energy transfer orbit from Mercury's aphelion to Venus. Some additional savings could be had by using Mercury flybys to pump the orbit out to Venus. The rocket capable of that operation has to be the *payload* of some other rocket. The demands are incredible, certainly beyond any unmanned mission ever flown.

There would be an energy savings if, like Apollo, a remote rendezvous took place, so that the return fuel for the interplanetary cruise did not have to be landed onto the surface of Mercury. This would help, but the demands would still be huge (a rocket that could perform the cruise would have to enter Mercury orbit no matter how you look at it).

Look, it's just not going to happen in our lifetime!

Posted by: dvandorn Nov 30 2005, 10:41 PM

Well, it *may* not happen in the lifetimes of the average members of this forum. But that all depends on the state of advancement of propulsion technology. I've seen some articles on plasma drive concepts that are being championed by, among others, Franklin Chang-Diaz, that could dramatically increase the amount of delta-V capacity a spaceship can drag along with it.

If we can develop bigger, better propulsion systems in the next 20 or 30 years, things that can give you constant acceleration for most of your flight (and not at measely 1/100th G levels, either), then you can tool around the Solar System in months when you used to need to spend years. Months or years when you used to need decades.

It's not like we will *always* be limited to push-real-hard-then-coast-for-years technologies. At least, I'm sincerely hoping not.

-the other Doug

Posted by: tasp Dec 1 2005, 02:42 AM

I was hoping that since Messenger was launched on a mid size rocket, and that a large part of the delta vee is from the grav. assists at earth Venus, and Mercury, a big Titan IV (or whatever the big launcher is now) could send a useful vehicle on a two way trip. The 'smash and grab' idea for a sample return I saw here is just starting to seem a little more doable, perhaps . . . .

Amazing to be looking at these (formerly) exotic trajectories, from Mercury sample returns to Pluto landers, it just keeps getting better all the time.

![]()

Posted by: BruceMoomaw Dec 1 2005, 10:22 PM

Actually, it might be doable with a smaller booster. The question is how fast a flyby speed at Mercury you're willing to put up with during the sampling. Messenger will make multiple gravity-assist flybys of Mercury to slow itself down in order to minimize the fuel it has to burn at Mercury Orbit Insertion, but that problem doesn't apply to a nonstop smash-and-grab sampling flyby. The question is the speed at which the collected particles can plow through the aerogel before the frictional heat ruins them for scientific analysis.

But if you are willing to make that sampling run during your first flyby of Mercury, then making your way back to Earth via Venus gravity-asssist flybys becomes much easier and shorter.

Posted by: BruceMoomaw Dec 12 2005, 09:21 PM

http://www.space.com/astronotes/astronotes.html : Messenger fired its big engine successfully for almost 9 minutes on Dec. 12 -- the last component of the craft that hadn't been operated until then. So everything works (except for occasional software collywobbles). Now if everything will just continue working...

Posted by: ljk4-1 Dec 14 2005, 07:45 PM

A thought from someone on another space list:

Will MESSENGER and Venus Express conduct any joint studies on Venus like Galileo and Cassini did with Jupiter in 2000? And if they can and do, what could they do together that they could not do alone?

Posted by: AlexBlackwell Dec 14 2005, 08:28 PM

It might be possible during the June 2007 flyby; however, MESSENGER won't be collecting science data during the October 2006 flyby (due to solar conjunction), so that opportunity is out.

Posted by: AlexBlackwell Feb 23 2006, 05:35 PM

MESSENGER Mission News

February 23, 2006

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

MESSENGER Lines Up for Venus Flyby

MESSENGER trajectory correction maneuver 10 (TCM 10) lasted just over two minutes and adjusted its velocity by about 1.4 meters per second (4.6 feet per second). The short-duration maneuver yesterday placed the spacecraft on track for its next major mission event: the first Venus flyby on October 24, 2006.

Having completed six successful small TCMs that utilized all 17 of the spacecraft’s thrusters, this latest maneuver was the first to rely on the four B-side thrusters. During this maneuver, the thrusters on the opposite side of the spacecraft reduced a build-up of angular momentum due to an unseen force that causes the spacecraft to rotate if left uncorrected. This maneuver was only the seventh actual TCM for MESSENGER; the spacecraft’s trajectory was so close to optimal after TCM 3 and TCM 6 that planned TCMs 4, 7 and 8 weren't necessary.)

The maneuver started at 11 a.m. EST; mission controllers at The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, verified the start of the maneuver within 11 minutes and 48 seconds, when the first signals indicating spacecraft thruster activity reached NASA's Deep Space Network tracking station outside Goldstone, Calif.

At the start of the maneuver, the spacecraft was 132 million miles (212 million kilometers) from Earth and 83 million miles (133 million kilometers) from the Sun, speeding around the Sun at 68,163 miles (109,698 kilometers) per hour.

For graphics of MESSENGER's orientation during the maneuver, visit the “Trajectory Correction Maneuvers” section at http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/the_mission/mission_design.html.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Earth Flyby Image Gallery Now Online

MESSENGER’s Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS) acquired spectacular images during the Earth flyby in August 2005, including a "film" of our home planet as it receded in the distance. Now, you can browse through the best of the MDIS flyby frames on the MESSENGER Web site!

Visit the MDIS Earth Flyby gallery at http://cps.earth.northwestern.edu/MESSENGER_20050802/.

Posted by: dilo Mar 22 2006, 08:52 PM

Flyby images are beautiful, thanks Alex.

Starting from one eof these pictures and using also the famous MRO moon image, I made these mosaics... is only a "petit divertissment", first one should be geometrically more correct, while second one is a tribute... ![]()

Posted by: angel1801 Mar 23 2006, 11:10 AM

This is because Mercury transits the Sun on November 8 (19:14 UT) to November 9 (00:15 UT). And transits can only occur at inferior conjunction ie when Mercury anf Earth line up in a straight line anf Mercury is at "New moon" phase. Mercury is too close to the Earth for a month or so before and after the inferior conjunction for realiable transmission of data.

Posted by: AlexBlackwell Mar 23 2006, 04:48 PM

Thanks, angel1801. I think I remember something like that from an Astronomy 101 lecture but my memory is hazy because I was at a frat party the night before.

Comm hiatus for solar conjunctions is a feature of many interplanetary missions. And I think you meant to write "Mercury is too close to the Sun..."

Posted by: ugordan Mar 23 2006, 05:06 PM

I'm lost. Isn't the next flyby that's not going to be taking any science a Venus flyby? If so, what's Mercury got with it?

I'm also a bit puzzled by this no-science policy. Why couldn't have they programmed the s/c to play the data back a couple of days/weeks later?

Posted by: Sunspot Mar 23 2006, 05:11 PM

That's what I was thinking too......

Posted by: AlexBlackwell Mar 23 2006, 05:16 PM

Take a number, ugordan. I was "lost" first.

Assuming angel1801 was referring to the upcoming Venus flyby, you're right, though rather than issuing two corrections, I gave him/her the benefit of the doubt and assumed he/she was making a general statement with respect to MESSENGER being in orbit around Mercury. That's my "Bruce excuse." In reality, I just wasn't paying too close attention.

Posted by: AlexBlackwell Mar 24 2006, 09:08 PM

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/status_report_03_24_06.html

MESSENGER Status Report

March 24, 2006

Posted by: antoniseb Apr 5 2006, 08:20 PM

Messenger is now further from the Sun than the Earth is. It will stay that way for several weeks, and then never again will it be that far from the Sun.

Posted by: abalone Apr 6 2006, 01:20 PM

MESSENGER Status Report

March 24, 2006

What is this mile you speak of??

Sorry to be so petty but there is no place for imperial units in any endevour that promotes itself as being either scientific or international, NASA needs to get a grip!!

Posted by: RNeuhaus Jun 24 2006, 04:52 AM

A new update news from Messenger status:

Mercury Messenger Probe Flips Sunshade Towards The Sun

http://www.spacedaily.com/reports/Mercury_Messenger_Probe_Flips_Sunshade_Towards_The_Sun.html

The Messenger spacecraft performed its final "flip" maneuver for the mission on June 21. Responding to commands sent from the Messenger Mission Operations Center at The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Md., through NASA's Deep Space Network antenna station near Goldstone, Calif., the spacecraft rotated 180 degrees, pointing its sunshade toward the Sun.

Rodolfo

Posted by: AlexBlackwell Jul 27 2006, 02:03 AM

If this has been mentioned already, pardon the repeat, but for those who do not have access to some of those hard-to-obtain journals, I just noticed the http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/the_mission/publications.html now has links to several of the references.

Posted by: AlexBlackwell Aug 3 2006, 09:27 PM

MESSENGER Mission News

August 3, 2006

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/

________________________________________________________

Happy Anniversary, MESSENGER!

Today marks the second anniversary of MESSENGER’s launch. “It’s still more than four and a half years to Mercury Orbit Insertion in March 2011, and there are many milestones between now and then,” says Dr. Sean C. Solomon, of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, who leads the mission as principal investigator. “But it’s worth pausing for a few moments today to appreciate how far we’ve come.”

And just how far has the spacecraft traveled since its Aug. 3, 2004, launch from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla.? Slightly more than 1.275 astronomical units (1 AU is Earth’s distance from the Sun). MESSENGER’s computers have executed 180,271 commands since liftoff, a time interval that includes seven major trajectory correction maneuvers.

“It’s been a busy two years,” says MESSENGER Mission Operations Manager Mark Holdridge, of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Md. “We’ve been by Earth and now we are headed for Venus, another major milestone in this mission.”

MESSENGER team members have been running tests all summer to make sure the spacecraft will operate as intended during the Venus flyby – the first of two swings past the clouded planet –scheduled for Oct. 24, 2006. There will be a 57-minute solar eclipse during that operation. So on Aug. 11, engineers will turn the spacecraft solar panels edge-on to the Sun and discharge the battery, much in the same manner that the power system will function during the Venus flyby, to verify that the system will respond appropriately.

Two weeks later, on Aug. 21, engineers will conduct a “star-poor” region test, pointing the spacecraft’s star tracker in a region of the sky that might be utilized during the Venus operations Holdridge says a similar test was conducted on July 26, “and we got a positive result from that test; the preliminary results look good.”

All in all, Holdridge says, all systems are functioning very well. “The spacecraft is very healthy, and the team is working hard to make this first flyby of Venus a success!”

For encounter details and graphics associated with the October maneuver, go online to http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/the_mission/MESSENGERTimeline/VenusFlyby1.html

________________________________________________________

MESSENGER Engineer Named AIAA Engineer of the Year

APL’s T. Adrian Hill, the fault protection and autonomy lead for MESSENGER, was recently named Engineer of the Year by the Baltimore chapter of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA). Each year, local AIAA chapters present this award to a member who has made significant contributions to the field of engineering. For more information, go online to http://www.jhuapl.edu/newscenter/pressreleases/2006/060623b.asp.

________________________________________________________

Where is Mercury?

Mercury's orbit is so close to the Sun that we can only see it from Earth either just before sunrise or just after sunset. For a diagram of the orbits of the inner planets, as they appear today, go online to http://btc.montana.edu/messenger/wheremerc/wheresmerc.php.

________________________________________________________

MESSENGER (MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) is a NASA-sponsored scientific investigation of the planet Mercury and the first space mission designed to orbit the planet closest to the Sun. The MESSENGER spacecraft launched on August 3, 2004, and after flybys of Earth, Venus and Mercury will start a yearlong study of its target planet in March 2011. Dr. Sean C. Solomon, of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, leads the mission as principal investigator. The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory built and operates the MESSENGER spacecraft and manages this Discovery-class mission for NASA.

Posted by: AlexBlackwell Aug 4 2006, 09:23 PM

MESSENGER Mission News

August 4, 2006

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/

______________________________________________________________________________

CORRECTION

The August 3, 2006, MESSENGER Mission News incorrectly stated that the spacecraft had traveled “slightly more than 1.275 astronomical units” since its August 3, 2004, launch from Cape Canaveral Air Station, Fla. In fact, since lift off MESSENGER has traveled nearly 1.2 billion miles in its orbit around the Sun.

The spacecraft is currently 1.285 astronomical units (AU) distant from the Earth (1 AU equals 93 million miles). To track MESSENGER’s journey, go online to http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/whereis/index.php.

_______________________________________________________________________________

MESSENGER (MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) is a NASA-sponsored scientific investigation of the planet Mercury and the first space mission designed to orbit the planet closest to the Sun. The MESSENGER spacecraft launched on August 3, 2004, and after flybys of Earth, Venus and Mercury will start a yearlong study of its target planet in March 2011. Dr. Sean C. Solomon, of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, leads the mission as principal investigator. The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory built and operates the MESSENGER spacecraft and manages this Discovery-class mission for NASA.

Posted by: AlexBlackwell Sep 16 2006, 12:36 AM

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/status_report_09_15_06.html

MESSENGER Mission News

September 15, 2006

Posted by: climber Oct 10 2006, 09:16 PM

A quick reminder : Messenger is only 13 days to Venus flyby.

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/

Posted by: mchan Oct 11 2006, 03:51 AM

Noteworthy. Too bad there will not be science observations on this flyby due to conjunction.

Posted by: odave Oct 11 2006, 12:41 PM

IIRC the trajectory of this flyby wasn't very interesting for science returns anyway. Though maybe they could try to image that http://www.unmannedspaceflight.com/index.php?s=&showtopic=3232&view=findpost&p=69368 ![]()

Posted by: ugordan Oct 11 2006, 01:27 PM

This view hardly qualifies as uninteresting: http://space.jpl.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/wspace?tbody=299&vbody=-236&month=10&day=24&year=2006&hour=07&minute=00&fovmul=1&rfov=30&bfov=30&porbs=1&showsc=1

Posted by: odave Oct 11 2006, 01:36 PM

Hmmm. I'll have to find out where I read what I read... ![]()

Posted by: ugordan Oct 11 2006, 01:40 PM

From what I've seen playing around in the Simulator the past few minutes, it's a very low phase inbound and very high phase outbound encounter. Maybe not very photogenic for global imaging as you'd prefer moderate phase angles (at least I do), but in terms of cloud observation tracking and similar stuff it could have been pretty nice.

Posted by: odave Oct 11 2006, 02:01 PM

That rings a bell, but I haven't been able to Google up anything to support what I recalled. Chalk it up to my http://www.unmannedspaceflight.com/index.php?s=&showtopic=1705&view=findpost&p=46514 syndrome... ![]()

Posted by: Jeff7 Oct 11 2006, 02:11 PM

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/

Ah good, it can act as Venus Express Express.

Posted by: dvandorn Oct 11 2006, 04:56 PM

That's OK, Dave -- just wait until it progresses, as it has with me, to the more advanced form, CRAFT...

-the other Doug

edit -- see, goes to show you, you were referencing a post of mine, and I totally had no memory of it... toD

Posted by: tuvas Oct 19 2006, 04:31 AM

Too bad it won't have much of a chance to do any photographing, but it's a good idea...

Posted by: RNeuhaus Oct 19 2006, 03:24 PM

Yes, Messenger's will fly-by on Venus on the day and night side of Venus and besides, now, Venus is close to conjunction superior to Earth along with Mars.

You can find good details by visiting the following Web Page http://http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/the_mission/MESSENGERTimeline/VenusFlyby1.html

Minimum altitude (approximate since the surface is not perfectly round) above Venus: 3,040.1 kilometers (1,889.0 miles) on October 24, 2006 8:33 am UTC

Maximum spacecraft speed relative to center of Venus:

12.378 kilometers per second (7.691 miles per second or 27,689 miles per hour)

Rodolfo

Posted by: helvick Oct 19 2006, 04:18 PM

You have a typo in the URL there - it should be:

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/the_mission/MESSENGERTimeline/VenusFlyby1.html

Posted by: BPCooper Oct 19 2006, 11:33 PM

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/the_mission/MESSENGERTimeline/VenusFlyby1.html

Are the animations mislabeled, or are they from the original flyby dates for Mercury arrival in 2009? They both say Nov. 2 2004 and were updated last year, post launch.

Posted by: RNeuhaus Oct 20 2006, 02:08 AM

Why not? The animations is of First Venus Flyby, then again Venus Flyby on June 6,2007, and finally two Mercury flyby (Jan 14,2008 and October 6, 2008) and March 18, 2011 is the Mercury arrival.

Rodolfo

Posted by: Holder of the Two Leashes Oct 20 2006, 02:51 PM

Don't forget the animation for the third Mercury flyby on 30 Sep 2009.

The top right panel on the link for the first Venus flyby clearly states, when you enlarge it, that the spacecraft will be out of communication with earth due to the proximity of the sun in the line of sight.

Things will be better on the second flyby, and you'd think that they should be able to come up with some kind of coordinated activity with Venus Express. After all, two capable spacecraft observing the same object from different vantage points ...

Posted by: JRehling Oct 20 2006, 05:51 PM

Actually, they are both close to opposition. Mars will be in superior conjunction next year, and Venus is never in superior conjunction.

Posted by: Holder of the Two Leashes Oct 21 2006, 04:12 AM

Mercury and Venus are in inferior conjunction when they are more or less between the earth and sun. They are in superior conjuction (as Venus is now) when they are pretty much behind the sun as seen from earth. Mars is simply in "conjunction" in this situation, because its conjuctions can only be superior. Mars and other outer planets are in opposition when they transit near midnight, being more or less overhead then.

Posted by: RNeuhaus Oct 23 2006, 03:28 AM

Tomorrow between 4-5 am, Messenger will be flying-by over Venus. I am still unclear about the Messenger path after seeing the flyby movies and pictures of Venus 1st Flyby. The pictures show that Messenger is coming from South Pole at about an angle of 60 degree to equotorial line. See the following picture:

The Meessenger approach to Venus side by side and it does not coincide with the above picture which shows that Messenger approach in about 85 degrees from the Sun to Venus.

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/the_mission/movies.html

According to the picture which shows Earth, Venus and Mercury orbit around the Sun from the top view.

I am still puzzled that Messenger will approach to Venus from Sun and not by side by side toward with the same orbit direction as Venus.

Rodolfo

Posted by: Holder of the Two Leashes Oct 23 2006, 04:04 AM

Well, the two diagrams do match up. The tick marks are a little more compressed looking in from the sun, but if you carefully trace by the intervals, you'll see in both cases that as viewed from Venus the spacecraft moves in from the sun moving westward and northward, before being flung back south. It still continues west on its departure.

It's necessary to pursue this path, flung backwards from the normal counterclockwise motion of the planets as viewed from north, in order to lose energy relative to the sun, and adjust the orbit inward toward Mercury. It is also necessary to go to high latitudes on Venus in order to adjust to the plane of Mercury's orbit.

Posted by: yaohua2000 Oct 23 2006, 02:21 PM

2006-10-23 02:21:05 UTC — 1000000 km

2006-10-23 05:24:28 UTC — 900000 km

2006-10-23 08:27:49 UTC — 800000 km

2006-10-23 11:31:05 UTC — 700000 km

2006-10-23 14:34:15 UTC — 600000 km

2006-10-23 17:37:14 UTC — 500000 km

2006-10-23 20:39:59 UTC — 400000 km

2006-10-23 23:42:21 UTC — 300000 km

2006-10-24 02:44:00 UTC — 200000 km

2006-10-24 05:44:07 UTC — 100000 km

2006-10-24 06:01:58 UTC — 90000 km

2006-10-24 06:19:46 UTC — 80000 km

2006-10-24 06:37:31 UTC — 70000 km

2006-10-24 06:55:12 UTC — 60000 km

2006-10-24 07:12:50 UTC — 50000 km

2006-10-24 07:30:24 UTC — 40000 km

2006-10-24 07:47:58 UTC — 30000 km

2006-10-24 08:05:50 UTC — 20000 km

2006-10-24 08:27:26 UTC — 10000 km

2006-10-24 08:34:00 UTC — 9044 km (2992 km above surface)

Note: geometric range, not corrected for light-time

Posted by: RNeuhaus Oct 23 2006, 03:04 PM

It's necessary to pursue this path, flung backwards from the normal counterclockwise motion of the planets as viewed from north, in order to lose energy relative to the sun, and adjust the orbit inward toward Mercury. It is also necessary to go to high latitudes on Venus in order to adjust to the plane of Mercury's orbit.

Good comments, I think a three dimensional graphic would help to view better. Also the above graphic is too small that I seems that after flyby Venus, Messenger would go away from the Venus toward Earth orbit. But, If there is a bigger (smaller scale) in a three dimensional, I would be able to see that after Venus fly-by, Messenger would go toward the South of Venus and little by little going toward on the counterclockwise. For the second fly-by in the June 6, 2007, Messenger will arrive at Venus comming from the North of Venus to South but on the opposite to Venus orbit direction? I see it is for slowing the speed as much as possible with the Venus gravitational pulling (from 13,500 km/sec at Venus 2 fly-by to 7,100 km/sec at Mercury 1 fly-by). But, when Messenger arrives at Mercury, it will be again flying the orbit around the Sun on the counterclockwise.

Rodolfo

Posted by: Holder of the Two Leashes Oct 24 2006, 12:40 AM

Yes, the emphasis on the second flyby would seem to be more toward reducing speed relative to the sun. The spacecraft will always be seen from the sun as moving eastward, giving a counterclockwise orbit as viewed from north to south. But Venus flinging it back will significantly reduce the spacecraft speed as seen from the sun (and microscopically increase the speed of Venus).

On the website space.jpl.nasa.gov you can see the approach (and departure) of Messenger in a broader scene up to a point. That point is 3:40 UTC on the 24th, with a sudden shift to a Venus centered approach line rather than sun centered for both planet and spacecraft. It will only show one snapshot at a given time at five minute intervals, but repeated entries will show the two closing in on each other.

Chose "MESSENGER" as seen from "above" with a selection of "60 degrees" field of view (make sure the field of view option is clicked) on this website and you'll see what I'm talking about.

Just about nine hours to go ...

Posted by: RNeuhaus Oct 24 2006, 02:41 PM

By now, I haven't found any internet refresh news. Let suppose that the flyby have occured today at around 4:30 am at EDT time.

How was the Venus 1 fly-by?

Rodolfo

Posted by: djellison Oct 24 2006, 02:44 PM

How could we possibly know? Venus, like Mars, is in conjunction. That is the reason there was no science planned for Messenger during this flyby - the spacecraft is totally out of touch.

Doug

Posted by: maycm Oct 24 2006, 03:09 PM

Why no science?

Surely Messanger could be programmed for observations well in advance for the flyby - even if it was unable to transmit the results until sometime aftwards?

Would this not be at least an opportunity to test run some of the instruments ahead of the eventual rendezvous with Mercury?

Posted by: djellison Oct 24 2006, 03:20 PM

There will be further chances to test the instruments out - but one could ask the same question of MGS, ODY and MRO at Mars during conjunction....why no science.

#1 reason - while you're out of touch you want the spacecraft to be as quiet as possible, so minimising the chance of anything going wrong and causing a safe event which may consume prop etc.

doug

Posted by: Phil Stooke Oct 24 2006, 03:20 PM

Why no science?

The question has been asked many times. Simply put, if you can't communicate with the spacecraft and the encounter is not the main focus of the mission, you can't afford to conduct complex operations. If anything goes wrong and the spacecraft enters safe mode you can't go to work on it, and the potential for fatal errors is too high. And... there's a second chance to do some Venus science later.

Phil

Posted by: RNeuhaus Oct 24 2006, 04:49 PM

And... there's a second chance to do some Venus science later.

Yes, at June 6, 2007 Messenger will have coordinations with VEX to conduct many science observations. It is a matter of time. This second flyby is a very important since Messenger will jump from Venusian orbit into to Mercurian orbit.

Rodolfo

Posted by: Sunspot Oct 24 2006, 05:23 PM

But MRO IS making daily observations during the conjunction period.

Posted by: djellison Oct 24 2006, 06:37 PM

Only a very limited ammount with two instruments in a steady orbit. To sequence fly-by observations is a much mroe involved and intensive operation. If Messenger does some Mag observations during this flyby, then that would be analogous to the MARCI/MCS obs of MRO during conjunction.

Doug

Posted by: djellison Oct 24 2006, 10:04 PM

Bloody hell :

MESSENGER swung by Venus at 8:34 UTC (4:34 a.m. EDT), according to mission operators at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Md. About 18 minutes after the approach, an anticipated solar eclipse cut off communication between Earth and the spacecraft. Contact was reestablished at 14:15 UTC (10:15 a.m. EDT) through NASA's Deep Space Network, and the team is collecting data to assess MESSENGER's performance during the flyby.

Posted by: nprev Oct 25 2006, 04:24 AM

![]() ...Doug, I assume "bloody hell" means "HELL yeah!" in American slang...I hope this is good news, although it seems a bit guarded...

...Doug, I assume "bloody hell" means "HELL yeah!" in American slang...I hope this is good news, although it seems a bit guarded... ![]()

Posted by: Bubbinski Oct 25 2006, 06:08 AM

I just saw something in the Florida Today "Flame Trench" blog that Messenger had an unexpected computer reset. I hope it's nothing serious.

Posted by: mchan Oct 25 2006, 06:13 AM

Bloody hell! And that is NOT HELL yeah!

Posted by: ugordan Oct 25 2006, 07:08 AM

Update on the flyby: http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/status_report_10_24_06.html.

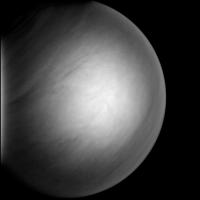

There's also an http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/the_mission/pictures/approach_venus.html of Venus taken by MDIS from 16.5 million km.

Posted by: nprev Oct 27 2006, 01:26 AM

Rog on the "BH", Doug & Mchan...just didn't see any reference to the anomaly in Doug's post, so I got confused.

In fact, I can't find any mention of this on Google News or on the Messenger website, which is kind of worrisome. I hope this doesn't mean that anomaly recovery has been interrupted by superior conjunction. Anybody have an update?

Posted by: ugordan Oct 30 2006, 07:15 PM

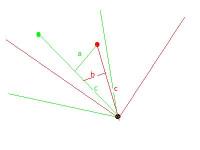

There's something weird with the http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/whereis/index.php#view_earth page. Here are two screenshots of the same simulated time:

Notice how Earth's position shifts from right of the Sun to its left in the second image. Even taking into account the second image appears slightly rotated CCW w/respect to the first, it still doesn't look fit. Earth appears at two different positions at once. A bug?

Posted by: remcook Oct 30 2006, 07:40 PM

Seems OK to me. Looks just like parallax when you move towards mercury in the centre of your view.

Posted by: ugordan Oct 30 2006, 08:06 PM

How can you have parallax if your viewpoint (MESSENGER) is fixed?

Posted by: remcook Oct 30 2006, 09:56 PM

hold a pencil in front of you and turn your head.

Posted by: ugordan Oct 30 2006, 09:57 PM

You do realize that by turning your head, you're shifting your eyes, do you? MESSENGER is a single, fixed point in the simulation. Only the look vector changes.

Posted by: remcook Nov 1 2006, 11:52 AM

yes, but I think it's probably a very similar effect that comes out of the simulations. Not sure though, but it looks like it. Angles stay the same, but the projection doesn't, because you look in a different direction, so your plane of projection has a different angle. Will try to make a drawing.

Posted by: remcook Nov 1 2006, 12:07 PM

Here's the drawing. green and red show two objects at different distances. lines show middle and edges of field-of-view. If you have a projection plane perpendicular to the middle line at a distance c, a will not equal b for the two cases. Not sure this is how exactly they made the plot though.

Posted by: ugordan Nov 1 2006, 04:06 PM

I'm not sure I get that plot, but I understand what you're saying about the distances. However, I'm talking about the angle between Earth-Sun-Mercury, see how it changes in the two instances. That does look like a bug. I have a fair amount of experience playing around in Celestia/Orbiter and never have I encountered such position shifts, even for large FOVs. To drive my point further, here are two plots from the Solar System Simulator:

http://space.jpl.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/wspace?tbody=399&vbody=-236&month=10&day=30&year=2006&hour=16&minute=00&fovmul=1&rfov=30&bfov=30&porbs=1&showsc=1

http://space.jpl.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/wspace?tbody=199&vbody=-236&month=10&day=30&year=2006&hour=16&minute=00&fovmul=1&rfov=30&bfov=30&porbs=1&showsc=1

If you disregard the rotation (the sim probably aligns to the target north axis), you can see how the angle stays the same and is consistent with the first screenshot I posted, viewing Earth. Earth stays on the same "side" of the Sun in both cases, as one would expect.

Posted by: Bjorn Jonsson Nov 1 2006, 05:17 PM

Having a fairly extensive experience playing around with 3D software and even writing a 3D renderer myself I cannot see how this could be anything but a bug. The views are supposed to show the Earth and Mercury as seen from Messenger at the same time and therefore the same location. The field of view is identical (or at least very nearly so), judging from Mercury's distance in pixels from the Sun. However, not only is the Earth's location relative to the Sun different in the two images, its 'distance' is also different and that difference is big. The field of view also isn't very wide (~30°) so distortion isn't significant.

Assuming the views generated by the http://space.jpl.nasa.gov/ are correct the view showing the Earth from Messenger is correct (or very nearly so) while the one showing Mercury is not.

Posted by: remcook Nov 1 2006, 06:01 PM

ah, I think I know what you mean now. sorry, I misunderstood you - I looked at the sun and Mercury, not the angles between them all.

edit - what I think I was trying to say is that if you have a flat projection plane you might get things distorted, whereas you have a spherical projection plane the angles would always stay correct. I guess the same problems occur with e.g. a fisheye projection. angles of things relative to eachother may change depending on where you aim it. But if the fov is not very wide...

Posted by: Malmer Nov 1 2006, 08:32 PM

it has to be a bug.

There is no way that any projection can move objects around in respect to each other that way.

it looks to me as if these pictures are rendered with an equirectangular projection (ordinary 3d camera) and that the position of the camera has changed. Im 99.9% sure.

they probably have some strange offset. (like if you move out from an object in celestia and then turn the camera to look at something else)

The simulations look s bit substandard to me... not like something that you would expect from a project that cost millions and millions of dollars.

Posted by: remcook Nov 2 2006, 08:42 AM

Had another think I see now I was just being plain stupid ![]() In my mind I had my projection plane some distance from the rotation point (Messenger), which would obviously give you a parallax. But maybe the programmer was similarly stupid

In my mind I had my projection plane some distance from the rotation point (Messenger), which would obviously give you a parallax. But maybe the programmer was similarly stupid ![]() Man, sometimes I wonder why i get up in the morning

Man, sometimes I wonder why i get up in the morning ![]()

Posted by: Phil Stooke Nov 3 2006, 02:37 AM

On the date in question the spacecraft and Venus were some little distance apart. It looks to me like one simulation was viewed from Venus and one from Messenger, just a simple mistake in entering the viewpoint before doing the rendering.

Phil

Posted by: ugordan Nov 3 2006, 08:26 AM

Nope. Not even Venus as viewpoint brings Earth to the other side of the Sun. http://space.jpl.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/wspace?tbody=399&vbody=299&month=10&day=30&year=2006&hour=16&minute=00&fovmul=1&rfov=30&bfov=30&porbs=1&showsc=1.

Posted by: ugordan Dec 13 2006, 04:22 PM

MESSENGER Mission News

December 2, 2006

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/status_report_12_02_06.html

Posted by: Littlebit Dec 13 2006, 04:44 PM

December 2, 2006

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/status_report_12_02_06.html

Interesting. The Venus post fly-by correction was originally scheduled for December 12. I wonder why they moved it up to December 2?

Posted by: tasp Dec 13 2006, 06:06 PM

IIRC, a similar change was made to the Voyager 1 (or was it 2?) flight plan post Jupiter.

It wound up saving some fuel as they were able to correct for some slight error sooner than had they waited for the error to have longer to operate.

Posted by: Greg Hullender Jan 23 2007, 11:38 PM

I see Messenger has just started its fourth orbit. (Yes, I know it's a silly milsetone, but I like the graphs.)

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/whereis/index.php#current_orbit

Given the shape of the orbit, that gravitational assist from Venus in June is going to be a whopper. I note also that we're within one year of the first Mercury flyby.

Posted by: NMRguy Jan 31 2007, 03:21 PM

That’s a mission fact that isn’t so apparent from the MESSENGER website front page. Sure, we still have over 1500 days before orbit insertion, but the Venus flyby/gravity assist in early June sends the craft careening towards Mercury with the first flyby occurring on January 14, 2008. About half of the hemisphere facing the sun is unexplored, and MESSENGER should get great views of it on the outbound.

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/the_mission/ani.html

Posted by: Greg Hullender Feb 4 2007, 08:14 PM

I was looking at the Messenger site, trying to figure out how many times Messenger will orbit Mercury before the first flyby, and I ended up constructing this table, which I thought I'd share:

Event SMA Period Orbits Date Total Orbits

Launch 1 365 1.00 8/3/2004

E1 0.809 266 1.69 8/2/2005 1.00

V1 0.724 225 1.00 10/24/2006 2.68

V2 0.539 145 1.55 6/5/2007 3.68

M1 0.507 132 2.01 1/14/2008 5.23

M2 0.466 116 3.09 10/5/2008 7.24

M3 0.435 105 5.10 9/29/2009 10.33

MOI 0.388 88 3/18/2011 15.43

(Hope that comes out looking right, given the tabs.)

First column is all the milestones in the mission. Second column is the semi-major axis of Messenger's orbit (in AU) AFTER each event. Third column is the period (in days) of that orbit. Fourth column is the number of orbits it makes before the next event. Fifth column is the date of each event. Last column is the total number of orbits before each event. (All these figures, except the orbit counts, come directly from the Messenger website.)

So, from this, I can see that Messenger will reach Mercury's orbit for the first time 145 days before the flyby -- on or around August 23 of this year.

That's a kind of cool milestone, I think. (Assuming I haven't messed up the figures somehow.)

--Greg

Posted by: AlexBlackwell Feb 5 2007, 08:15 PM

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/status_report_02_05_07.html

MESSENGER Mission News

February 5, 2007

Posted by: JRehling Feb 7 2007, 07:21 PM

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/the_mission/ani.html

While the first two flybys alone theoretically expose almost all of Mercury's surface to Messenger's cameras, a lot of the antiMariner terrain will be near the limb during the second and third flybys. The first one will indeed represent a lot of filling in the map that Mariner 10 began. By the time the main mission begins, we will have a decent global map of the planet, but with some areas covered only in low resolution. After 32 years of waiting, though, 11 months for a big chunk of new coverage seems like almost nothing.

Posted by: AlexBlackwell Feb 20 2007, 04:27 PM

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/status_report_02_20_07.html

MESSENGER Mission News

February 20, 2007

Posted by: NMRguy Mar 19 2007, 04:25 PM

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/status_report_03_19_07.html

MESSENGER Mission News

March 19, 2007

A new mission update. MESSENGER's Energetic Particle and Plasma Spectrometer (EPPS) has been fired back up, and both components are working nominally. Also, the team notes that yesterday (March 18) it was 4 years to the day for Mercury insertion.

Posted by: NMRguy Apr 2 2007, 08:36 PM

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/status_report_04_02_07.html

MESSENGER Mission News

April 2, 2007

Two-Fifths of the cruise duration is now behind us. A somewhat arbitrary landmark (spacemark?), but the MESSENGER team uses this as an opportunity to let us know what they are planning in June. Perhaps we'll get a nice combined NASA/ESA press release after the flyby? Time will tell.

"Planning is now underway to use the second Venus flyby on June 5 to complete final rehearsals for three Mercury flybys. Those flybys, assisted by four deep space maneuvers, will slow the spacecraft sufficiently for Mercury orbit injection on March 18, 2011.

The upcoming planetary encounter also offers a variety of opportunities for making new observations of Venus’ atmosphere and cloud structure, space environment, and, perhaps even the surface. All of the MESSENGER instruments will be trained on Venus during the encounter.

* The MDIS will image the night side in near-infrared bands, and color and higher-resolution monochrome mosaics will be made of both the approaching and departing hemispheres.

* The UltraViolet and Visible Spectrometer, part of the probe’s Mercury Atmospheric and Surface Composition Spectrometer (MASCS), will capture profiles of emissions from atmospheric species versus altitude on both the day and night sides as well as observations of the exospheric tail on departure.

* MASCS’s Visible and InfraRed Spectrograph will observe the planet near closest approach to assess the chemical composition of clouds. It may also detect near-infrared returns from the surface.

* The MESSENGER Laser Altimeter (MLA) will measure Venus’ brightness at 1064-nm by using its pulse return detector as a passive sensor. MLA will also pulse its laser in an attempt to measure the range to one or more cloud decks for several minutes near closest approach.

* The Magnetometer will characterize the magnetic structure of the Venus bow shock and draping of the interplanetary magnetic field over Venus’ ionosphere while the Energetic Particle and Plasma Spectrometer will observe charged particle acceleration and plasma flows associated with the bow shock.

The Venus Express mission of the European Space Agency is currently operating in an elliptical polar orbit about Venus, and MESSENGER’s June planetary encounter together with the ongoing observations by Venus Express will permit unique observations of the Venus-solar wind interaction. To understand fully how the solar wind plasma affects and controls the Venus ionosphere and nearby plasma dynamics, simultaneous measurements are needed of the interplanetary conditions and the particle-and-field environment at Venus. The combined MESSENGER and Venus Express observations will be the first opportunity to conduct such two-spacecraft measurements."

EDIT: Don Merritt over at VEX Science Operations states that http://www.unmannedspaceflight.com/index.php?showtopic=4011&st=15&p=87153&#entry87153 of the joint science will occur in mid-June. I'm looking forward to it.

Posted by: NMRguy May 2 2007, 09:51 PM

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/status_report_05_02_07.html

MESSENGER Mission News

May 2, 2007

MESSENGER completed a burn to set up the rapidly approaching second Venus flyby. Not everything is smooth sailing, however, as spacecraft "jitter" was detected during the burn, resulting in a slightly less than ideal trajectory. Scientists will analyze the attitude control system and tracking data to figure out the source of the problem, hopefully finding a solution before the May 25 trajectory correction maneuver that will put MESSENGER in the intended aim point of 337 kilometers above the surface of Venus.

Let's hope the engineers figure out the flutters in the spacecraft sooner than later.

Posted by: OWW May 26 2007, 09:20 PM

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/status_report_05_25_07.html

MESSENGER Mission News

May 25, 2007

The MESSENGER trajectory correction maneuver (TCM-16) completed on May 25 lasted 36 seconds and adjusted the spacecraft’s velocity by 0.212 meters per second (0.696 feet per second). The movement targeted the spacecraft close to the intended aim point 337 kilometers (209 miles) above the surface of Venus for the probe’s June 5 flyby of that planet.

The maneuver started at 12:00 p.m. EDT. Mission controllers at The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Md., verified the start of TCM-16 about 7 minutes later, when the first signals indicating thruster activity reached NASA’s Deep Space Network tracking station outside Madrid, Spain.

“Today’s operation completed just as planned,” says Mission Operations Manager Andy Calloway of APL. “All subsystems were nominal going into the maneuver, and the burn cutoff occurred right at the expected time. Now that TCM-16 is behind us, we are focused on loading the Venus flyby command load to the spacecraft next week.”

Posted by: nprev May 26 2007, 10:35 PM

BTW, the Messenger site has a much improved interactive mission timeline well worth a look:

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/the_mission/MESSENGERTimeline/TimeLine_content.html

Looks like this coming January 14th we'll get to see unexplored territory not imaged by Mariner 10...go Messenger! ![]()

Posted by: AlexBlackwell May 30 2007, 08:51 PM

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/news_room/status_report_05_30_07.html

MEDIA ADVISORY: M07-060

May 30, 2007

Posted by: Greg Hullender Jun 1 2007, 08:37 PM

I note that they've updated the Messenger site to show Venus instead of Mercury.

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/whereis/index.php#view_mercury

Even though the tag is still CALLED "view_mercury," of course. :-)

--Greg

Posted by: Littlebit Jun 4 2007, 01:58 PM

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu

Posted by: CAP-Team Jun 4 2007, 02:54 PM

The quote above suggests that the spacecraft would actually be visible to observers..

Would be nice, but I don't think you can see the spacecraft passing Venus

Posted by: Holder of the Two Leashes Jun 4 2007, 11:07 PM

Looking forward to "Mercury Flyby 1" on the web site countdown clocks in the next couple of days.

Here's wishing a successful Venus flyby with good science.

Posted by: RichardLeis Jun 4 2007, 11:17 PM

I am not sure if this is planned, but I would love to see a flyby movie like the MESSENGER team created for the August 02, 2005 Earth flyby. I cannot stop playing that movie over and over again...

I was surprised during a recent search for Venus global views by how few there seemed to be. Maybe I am just missing the good ones. I am so excited to see Venus fill a MESSENGER camera view.

Posted by: elakdawalla Jun 5 2007, 12:08 AM

I can confirm that the MDIS team does have an outbound movie planned to about 30 hours after closest approach. They'll be using 3 filters: one at 415 nm that should show the clouds pretty well, and two near-infrared wavelengths that they hope might get through to the surface (I have my doubts, but I can't fault them for trying; I'm keeping my fingers crossed.)

I have more details...later...after I get my story on the flyby posted tomorrow.

--Emily

Posted by: lyford Jun 5 2007, 12:44 AM

I agree, these videos are an extra benefit of these complicated multiple flyby gravity assist missions. After years of watching Star Trek, it's finally nice to really see the planets zoom by (albeit not in real time...)

I would like to see one of these movies start with the planet as a a point of light and zoom by until it fades to a point again.... some day!

Posted by: RichardLeis Jun 5 2007, 04:59 AM

Thanks for the info, Emily. Looking forward to reading your report, and to the first images.

Yes, that would be great!

Posted by: edstrick Jun 5 2007, 07:36 AM

"... was surprised during a recent search for Venus global views by how few there seemed to be. Maybe I am just missing the good ones..."

Few missions to Venus have done imaging. Mariner 10 was the first, Soviet Venera 9 and 10 orbiters took limited data, not full disk. Pioneer Venus Orbiter took extensive "Imaging Cloud Polarimeter" camera data including a lot of whole disk coverage but that's increasingly forgotten and may not be available, even from the NSSDC.. worth investigating. Galileo got some nice full disc images but a very limited amount. That's it, so far, besides Venus Express.

Posted by: tedstryk Jun 5 2007, 02:27 PM

I have been told that they are slowly working to put the PVO clould photopolarimeter on CD-ROM, but that right now it is only available in extremely arcane formats.

Posted by: gndonald Jun 5 2007, 03:52 PM

Here's wishing a successful Venus flyby with good science.

I've just checked out the site and they seem to be showing both the 'Venus Flyby' and 'Mercury Flyby' captions with the clock showing the time to the Mercury flyby, hopefully there will be a site update soon.

Posted by: Littlebit Jun 5 2007, 06:14 PM

Is the number of images released by the VE program still in the single digits?