Printable Version of Topic

Click here to view this topic in its original format

Unmanned Spaceflight.com _ Saturn _ Voyager 1's Rhea

Posted by: Bjorn Jonsson Nov 7 2008, 12:54 AM

Back in 1980 Voyager 1 flew by Rhea at a distance of 59,000 km. The flyby was over the high northern latitudes so these images still represent the best coverage available of Rhea's north polar region. This was a high-speed flyby and Voyager's camera was a vidicon camera so it was much less sensitive than CCD cameras. During this flyby special image motion compensation was used for the first time by the Voyagers by rotating the entire spacecraft. This technique was subsequently used extensively by Voyager 2 at Uranus and Neptune; without it the highest resolution satellite images would have been hopelessly smeared due to the long exposure times required. I wonder if this was the first time ever this technique was used - does anyone know?

Not all of the hi-res Rhea images were obtained using this technique but those that were are superior in quality compared to the other images; after some processing they are almost 'Cassini-like'. They are sharper and much less smeared than the other images.

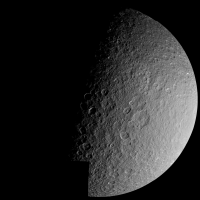

The image below is a mosaic of 10 of these motion-compensated images obained at a range of ~75,000-85,000 km. I used the calibrated and geometrically corrected Voyager dataset. Because this was a high-speed flyby the viewing geometry changed rapidly so it is difficult and maybe impossible to mosaic these images using 'conventional' methods without ugly artifacts. I got around this by reprojecting everything to 10 simple cylindrical maps and mosaicking these maps. This resulted in a map that had some seams since the viewing geometry information I used wasn't 100% accurate (I had to reverse engineer most of the geometric parameters). I removed the seams and made some cosmetic enhancements in Photoshop. This means that there are very slight inaccuracies where the seams were located (e.g. very small craters may be missing or 'double'). The final step was to render the resulting map on a sphere. As previously indicated the viewing geometry varied rapidly; the geometry I used when rendering was fairly 'typical'. This is the result:

The resolution of this image is similar to the resolution of the original images (~0.8 km/pixel) although some very small scale details appear slightly more blurred due to all of the resampling steps implicit to the method I used to make this image. A mosaic of these images that was made soon after the Voayger 1 flyby is fairly well known but it is has some ugly seams and brightness discontinuities.

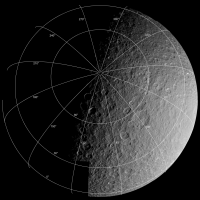

The smaller image below has a lat/lon grid to show the viewing geometry:

Close inspection reveals that the lat/lon grid appear 'outside' some parts of the limb. This is because in these places the imaging coverage doesn't extend far enough to the south.

Posted by: Hungry4info Nov 7 2008, 02:42 AM

That very image of Rhea captivated me when I was younger, or rather, before Cassini. It amazed me how beaten up that moon looked, and how crisp that image is. I suppose now with Cassini, I've gotten used to higher standards.

Posted by: dvandorn Nov 7 2008, 02:47 AM

The Lunar Orbiter spacecraft used motion-compensation built into the internal camera platform to obtain non-smeared images during low-orbit photographic operations. This system failed on L.O. 1 (a sensor that measured the rate a which the surface passed beneath the camera failed), and so most of the images from its low orbit are hopelessly smeared.

As for using physical movement of the entire spacecraft for motion compensation, the first example of that I can recall was on a manned spacecraft -- Stu Roosa used the technique after the Hycon camera failed on Apollo 14 so that he could acquire needed planning imagery for the eventual Apollo 16 Descartes landing site. In that case, he set the CSM into a special "orbital rate" mode to keep it aligned with a specific point on the lunar surface and took the photographs with a Hasselblad camera fitted with a 500mm lens.

-the other Doug

Posted by: tasp Nov 7 2008, 03:54 PM

Spacecraft motion was used serendipitously by an early Soviet era lunar lander to generate image pairs for 3D analysis of the surface features. The craft shifted (for reasons unknown, IIRC) between imaging sessions, and the resulting pictures had a sufficient baseline for the effect.

Posted by: Phil Stooke Nov 7 2008, 10:38 PM

That was Luna 9... but it's not really the same kind of thing we're talking about here.

Luna 9 also carried three ingenious dihedral mirrors to provide six image strips across the surface. By comparing the geometry of the surface seen in those images with the main panorama, some topographic data could be retrieved. A topo map was drawn from all this. More mysterious is the Luna 13 topo map which had no apparent data source except - just possibly - photoclinometry, and is more likely to be an educated guess.

Phil

Posted by: tedstryk Nov 7 2008, 11:02 PM

Luna 9 also carried three ingenious dihedral mirrors to provide six image strips across the surface. By comparing the geometry of the surface seen in those images with the main panorama, some topographic data could be retrieved. A topo map was drawn from all this. More mysterious is the Luna 13 topo map which had no apparent data source except - just possibly - photoclinometry, and is more likely to be an educated guess.

Phil

Phil, both Luna 9 and Luna 13 shifted somewhat while operating on the lunar surface. As a result, there is a slight amount of parallax. The other factor is that the changing illumination angle from panorama to panorama probably provided much of the topographic data as well.

Powered by Invision Power Board (http://www.invisionboard.com)

© Invision Power Services (http://www.invisionpower.com)