Printable Version of Topic

Click here to view this topic in its original format

Unmanned Spaceflight.com _ Chit Chat _ Pluto System Speculation

Posted by: Webscientist Jul 17 2015, 09:20 PM

My first impression was that the bright heart (made of frozen CO and not CO2...) looked like a "banquise" or an ice pack.

The black patches along some limits of the polygons seem to be in line with my initial assumption according to which there is a layer of liquid hydrocarbons (methane, ethane...) beneath this bright uniform crust.

At what depth?...

Possibly the largest reservoir of liquid hydrocarbons is hiding beneath this intriguing area! Who knows?

That's my bet!

Posted by: Sherbert Jul 17 2015, 11:32 PM

Lots of good suggestions for what is happening at Tombaugh. Gladstoner you have marked ground zero for the beginning of Charon's grazing impact. In the You Tube video stop it at 34 seconds. The depression and shock wave effects have piled up the mountains to the side of a deep circular depression, its rim wall peppered with sublimation features that look like golf bunkers. The mountain that looks like a Cathedral in this view is gigantic. We have seen before how moving images make perspective and detail easier to see and I suspect Alan has seen that and added it to improve the image presentation.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ydU-YrG_INk

So some thoughts following a lengthy perusal of this avalanche of information.

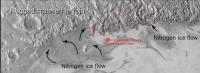

This shot is of the very tip of the Ice Cream cone part of Tombaugh. That ice cream cone is made up of frozen Carbon Monoxide. Imagine some giant bucket of fluid Carbon Monoxide was poured on top of the existing surface of Pluto, which is a frozen Nitrogen/Methane ice layer on top of a Water Ice layer beneath. Eventually, all fluid flow stops and it freezes. The deepest point of Charon's impact is marked by the crown of the Carbon Monoxide contour map. Towards the top of the Sputnik Plain image, there is a large slightly brighter, circular area which appears to be higher and hence colder than the more Southern areas of the Carbon Monoxide Ice sea/cap, which reflects that map nicely. It is noticeable the cracks are shallower and devoid of the hills/mounds and with very few areas of dark material. At its crown is a lonely dark spot. Sublimation pit, sinkhole, geyser? No Idea.

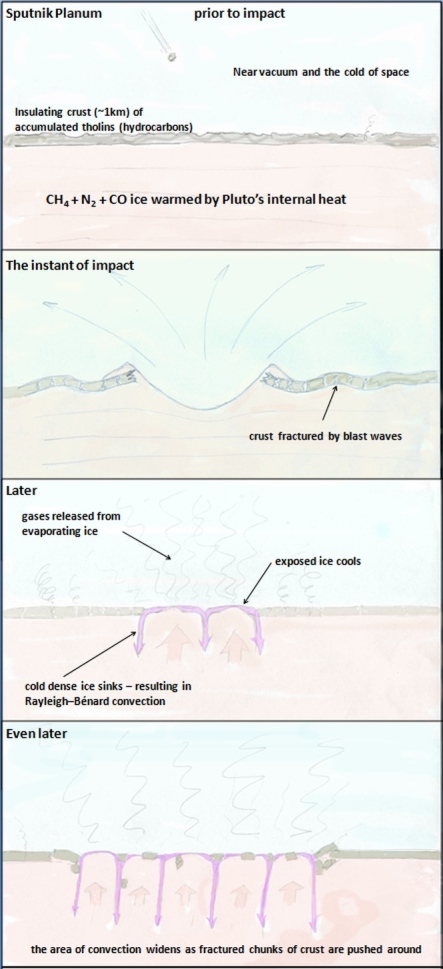

Beneath this area's now highly impact and shock compressed surface, it may have triggered a phase change in the "bedrock" Water ice below. This releases heat and starts to warm the N2/CH4 ice mixture from below, adding to the heat from the initial impact, superheated atmosphere and shock wave, from above. Whether its enough to liquify the mixture is an open question, but convection and sublimation will occur within such "warm", porous ices. If considerable amounts of gas are trapped below the CO ice sheet the expansion of gas could create enough pressure to create the polygonal pattern.

Where cracks appear in the ice, probably forced open by the pressure from below, the Methane and Nitrogen gas are released at the surface where they are exposed to a very low pressure, gaseous Carbon Monoxide, together with UV and Cosmic Radiation. Throw in a bit of micron sized interplanetary dust, result, lots of organics, hydrocarbons, Tholins, and PAHs, which are cooked to a dark brown sludge. It may only be millimetres or centimetres thick, but the albedo contrast is stark making its distinction from shadow, difficult.

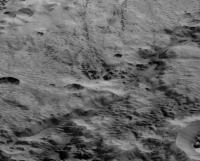

The escaping Methane and Nitrogen gas will soon freeze as an upside down icicle. Of course from long cracks, or confluences of cracks, hills, ridges and mounds would form, like growing crystals in a saturated fluid. The fact their height seems to be limited indicates they are probably not made of Water ice. Where the ice sheet is thinner, at the margins and towards the South, it is easier for the cracks to form and expand. We see many places where bits of the original underlying terrain show through, either completely or as surface topology. The nature of the original terrain can be seen in the "Ropey Mountains" far to the South, where wind, sublimation, frost deposition and thermal stress have created swirling patterns of valleys and ridges, on top of larger structures of swirling mountain chains separated by immense crevasses and canyons. Sublimation landscapes appear to show this repeating pattern on multiple scales, from micron to kilometres, as seen here and at 67P.

Lets consider Charon, possibly formed as a moon of Uranus, where, in this part of the Solar System, the predominant ices are Water and Carbon Monoxide. The young Charon, possibly undergoing tidal heating from Uranus, may have had a liquid, Carbon Monoxide/Water mixture, ocean below an outer rock hard, sintered, Water ice crust. That freezing out of the Water from the mixture to form the crust, may have concentrated the Carbon Monoxide to the point of separating the two. On its way towards Pluto that crust would have got, colder harder and even more brittle not to mentioned cracked and weakened.

Charon hits Pluto in a glancing blow, brittle ice crust cracks and shatters into huge Water ice chunks, some of which end up strewn across the surface of Pluto as mountains, some escape into orbit. The liquid ocean pours out of the broken shell in a giant flood filling the impact basin with liquid Carbon Monoxide, and liquid Water formed during the heat and pressure of the impact. At the deepest point, the subsequent freezing ice expands to create the central mound. When we see the "toes" at the Northern rim of the ice cream cone, I am expecting to see fjords and canyons carved in the bedrock Water Ice pushed up and ahead of the impact, a landscape similar to that Glacier picture earlier, as Carbon Monoxide/Water ice glaciers, lubricated by Nitrogen and Methane from beneath, carve the landscape.

Evidence for prevailing winds creating the opportunity for aeolian deposition in the lea of cliffs, ridges, hills, mountains and canyons, strongly suspected this and its nice to see some evidence. The comparison to the size of Earth's atmosphere is amazing, Pluto's is bigger than Earth's atmosphere now, it was surely way larger in the past given the modelled loss rate of 500 tonnes a second. The image I most want to see is the one that fits in the corner of the L. That will have that humungous mountain in it.

Finally would it be fair to compare these images and their resolution to an old B&W cathode ray television and the later highest resolution images to a Full HD 1080P TV. It seems about right, in which case this is going to get even more astounding. What a place! ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Posted by: lars_J Jul 17 2015, 11:59 PM

Sherbert, I don't think your fanciful explanation (a grazing impact of Charon created the landscape) takes into the account the TITANIC amounts of energy involved in two planetary bodies of this scale meeting at a speed that exceeds Pluto's escape velocity.

If Charon had a grazing impact with Pluto, a significant part (or almost all) of Pluto's surface would be completely altered by the energy involved, and the ejecta that would rain down on both bodies for an extended time. This would not just leave a nice flat plain and valley. It would not leave a visible scar that would allow you to trace the impact. Not even close.

Posted by: Sherbert Jul 18 2015, 12:17 AM

You are right it is fanciful, its speculation to stimulate discussion and ideas.

Posted by: nprev Jul 18 2015, 12:19 AM

Agreed.

Such speculation is fun, but there's something to be said for patience in terms of waiting for all the observations to be received as well. We've seen just a tiny amount of the anticipated data thus far, and it's possible--even likely--that more unexpected features are yet to come which will allow formation of much better hypotheses. ![]()

Posted by: Sherbert Jul 18 2015, 12:28 AM

Most definitely!

Posted by: Hungry4info Jul 18 2015, 12:34 AM

Besides, if Charon were to "hit" Pluto at a glancing blow, and wind up intact in a capture orbit, that orbit is already unstable by definition. I would expect Charon and Pluto to merge shortly afterward.

Posted by: Sherbert Jul 18 2015, 12:45 AM

So would I.

Posted by: atomoid Jul 18 2015, 12:50 AM

but since there's not enough data yet there's still room to get fanciful.. so along those lines, if a smaller ex-moon(s) of indeterminate size and composition were to deorbit as it deformed into a diffuse rubble pile that would tend to reduce its monolithic 'impact' legacy as it eventually and more gently joined with Pluto in the post-cratering epoch, depending upon how much of the surface is composed of volatiles that could be liquified by whatever magnitude of energy that may entail, there may be any of all sorts of possible crustal rearrangement resulting in chaotic jumbling of upturned 'mantle' blocks and plains, and all within the 'recent' past, though should such a scenario leave obvious traces on the orbits of the other moons to be ruled out?

Posted by: Sherbert Jul 18 2015, 12:55 AM

I would like to see some higher resolution images from Charon's North Pole, before I speculate further.

Posted by: Mongo Jul 18 2015, 01:00 AM

Here are the top ten known KBOs with their diameters, with their major moons:

Pluto (2370 km) : Charon (1208 km)

Eris (2326 km) : Dysnomia (685 km)

Makemake (1430 km)

2007 OR10 (1280 km)

Haumea (1920 x 1540 x 990 km) : Hi'iaka (310 km), Namaka (170 km)

Quaoar (1110 km)

2002 MS4 (934 km)

Orcus (917 km) : Vanth (378 km)

Salicia (854 km) : Actaea (286 km)

2002 AW197 (768 km)

Half of the ten KBOs are known to have large satellites! The trend continues among smaller KBOs (allowing for the observational difficulties). Given how common large satellites are around KBOs, I have to think that they formed almost automatically as part of the main KBO formation, as mini-planetary systems. Pluto/Charon would be no exception, in my opinion.

Maybe their isolation in the outer reaches of the Solar System means that their formation was mostly left undisturbed, unlike the chaotic and energetic inner Solar System. So any growing satellites were left in orbit around their primary, without being perturbed away from, or into, them.

Posted by: Aldebaran Jul 18 2015, 01:24 AM

I feel like a kid at Christmas time eagerly awaiting the unwrapping of the presents.

Water ice "bedrock: has a density of 0.92, Nitrogen about 1.02 and frozen methane about 0.52. At Pluto's calculated maximum internal pressure, we can say with some confident that water ice would exist as orthorhombic Ice (XI) or possibly some hexagonal ice. There are no major consequences of phase transitions (under normal conditions).

It's not difficult to understand that frozen methane, which behaves like a glass at Plutonian temperatures, would tend to upwell if it ends up below the surface due to impacts, subduction etc.

It's question of how far out of the box you can reasonably think. As Nprev says, there is a vast amount of data yet to come which could change the way we look at Pluto very quickly. So much is tentative.

Posted by: Jaro_in_Montreal Jul 18 2015, 01:57 AM

OK, so how's this for "reasonably far out of the box" ?

1) The Pluto/Charon system orbit is obviously very different from the "regular" planets.

2) The totally unexpected surface morphology of Pluto - almost devoid of craters - is likewise very different from solid bodies (moons) in the outer Solar System.

In other words, Pluto/Charon don't fit.

Ergo, like other "Sednitos", they may be alien worlds captured by the Sun from a passing star:

How Sedna and family were captured in a close encounter with a solar sibling

Lucie Jilkova, Simon Portegies Zwart, Tjibaria Pijloo, Michael Hammer

(Submitted on 9 Jun 2015)

Posted by: Sherbert Jul 18 2015, 02:05 AM

Leaving aside how it got there, the Carbon Monoxide ice cap is there on top of Nitrogen, Methane, possibly Neon, sitting on a "bedrock" of Water ice. The Ralph Methane map showed high levels of Methane above the North Pole and the Tombaugh Region and not really anywhere else. From the ideas and figures in other posts the burning question, "is there liquid under the ice cap?"

I'm guessing temperatures in Pluto's Northern Hemisphere on July 14th could be equated to mid July here on Earth. Pluto is about a quarter of the way through it's Northern Summer. So for the Pluto we see in these images, at the moment the temperature is approaching the top of the temperature range near the surface, a time when activity in the atmosphere and on the surface is going to be near its peak. How much of the Methane Ralph shows is on the ground and how much in the lower troposphere? That might have a bearing on localised greenhouse heating. With so many volatile mixtures with triple points around these temperatures, local temperature conditions, microclimates, are going to affect the composition of the surface ices and their physical properties. The team say with more detail they will be able to address these questions. That's going to be a real eyeopener as to whats going on.

With Pluto's axial tilt the highest temperatures are towards the Poles. The Tombaugh region seems to be the quickest route for warmer saturated atmosphere to the North to get to the cold South, but its sort of like a funnel, which would speed up the wind even more. Cold air would try to replace it from the South and meet somewhere in the middle where Charon's gravitational influence is also not to be ignored. Jupiter's Red spot comes to mind. Those polygonal structures are just like windblown ice formations on Earth, however on Pluto, that "hurricane" could last for half a Pluto orbit, over a hundred years. Thats going to leave a significant landmark on the surface.

Posted by: Mongo Jul 18 2015, 02:24 AM

1) The Pluto/Charon system orbit is obviously very different from the "regular" planets.

2) The totally unexpected surface morphology of Pluto - almost devoid of craters - is likewise very different from solid bodies (moons) in the outer Solar System.

In other words, Pluto/Charon don't fit.

Ergo, like other "Sednitos", they may be alien worlds captured by the Sun from a passing star:

While Pluto's orbit is unlike that of the "regular" planets, it is very typical of the "plutinos", which are, like Pluto, in a 3:2 resonance with Neptune. There are a great many such objects, of which Pluto is merely the largest.

They were originally in closer orbits to the Sun, but would have been swept up by Neptune as it moved outward and trapped in the 3:2 resonance.

Sedna's unusual orbit makes an extrasolar origin possible, but Pluto's orbit looks quite typical of the numerous objects that formed in the inner Kuiper Belt.

Posted by: Michael Hoopes Jul 18 2015, 02:31 AM

Hi everyone- I'm new to this enterprise of Plutonian speculation; could someone direct me to a source that has decent information about its potential to have a magnetosphere?

I'm trying to make sense of that heart shape, as it extends, saddle-like, around the southern pole. Alternatively, could there a possible gravitational influence involving Charon, as I think the "heart" is bisected opposite of the tidally-locked, Charon-facing prime meridian? Could it be a reverse marker of the heart's proportion of sun-facing time, given its quite complex solar orbital attitude?

Or...are these just adorable newbie intuitions and/or possiible misconceptions that have already been addressed in this forum?

Thanks,

Mike

Posted by: dvandorn Jul 18 2015, 03:48 AM

Kewl! Good to have a thread where we can speculate wildly. (ADMIN: With some restraint please. ![]() )

)

I'm wondering why the CO ice is all in Tombaugh Regio on the lit side of the planet. What would cause CO ice to gather just there? Altitude? Temperature? Is there a liquid CO "aquifer" underneath that only wells up here?

Remember that the area is getting the most insolation it will get during the northern summer. Yes, it gets more direct sunlight when the sun is high over the equator, but only for half a Plutonian day, so overall right now, even at a lower angle of incidence, it's getting insolation continuously. So it's not exactly a cold sink.

I think you have to start getting your head wrapped around the 248-year cycle of seasons on Pluto. It spends more than 50 years in each season, and more than a century of continuous insolation on each pole. Cold sinks are going to appear in odd places, build up ices, and sublimate back off as this cycle continues. And I'm thinking that each set of seasons are unique -- topography changes, ice deposition occurs in different places due to vagaries of wind and even weather -- so major ice depositions might occur in different places in different years.

Maybe the CO ice is a remnant of a major deposition that occurred in the best cold sink available on what was then the dark side when a big exposure of CO ice sublimated relatively quickly from the southern hemisphere? And the other ices deposited at the time have preferentially sublimated since the northern hemisphere began its summer, leaving only the harder-to-sublimate CO ice? If so, what around here sublimates more easily than CO ice? And maybe the pitted surface at the southern edge of Sputnik Planum is an example of where those other ices puffed out, leaving holes in the CO ice?

Also -- hitting the various things that have been crossing my mind -- if Pluto is losing 5 tons of nitrogen an hour to space, over four billion years that amounts to nearly 163 and half trillion tons of nitrogen, if that's been a relatively consistent loss rate. How many tons of Pluto is left? How much of the original body has been blown away? And how much more of other lighter elements might have been lost earlier in Pluto's history?

And, to answer my own question, a quick search shows me that Pluto has an estimated mass of 13 quintillion tons. A quick calculation tells me that the amount of nitrogen lost (again assuming a consistent loss rate) is 1.25e-5 percent of Pluto's current mass. So, I guess maybe not so much... sounds like a heck of a lot, though!

-the other Doug

Posted by: surbiton Jul 18 2015, 03:56 AM

MOD NOTE: Post moved from NH near encounter thread.

Pluto (2370 km) : Charon (1208 km)

Eris (2326 km) : Dysnomia (685 km)

Makemake (1430 km)

2007 OR10 (1280 km)

Haumea (1920 x 1540 x 990 km) : Hi'iaka (310 km), Namaka (170 km)

Quaoar (1110 km)

2002 MS4 (934 km)

Orcus (917 km) : Vanth (378 km)

Salicia (854 km) : Actaea (286 km)

2002 AW197 (768 km)

Half of the ten KBOs are known to have large satellites! The trend continues among smaller KBOs (allowing for the observational difficulties). Given how common large satellites are around KBOs, I have to think that they formed almost automatically as part of the main KBO formation, as mini-planetary systems. Pluto/Charon would be no exception, in my opinion.

Maybe their isolation in the outer reaches of the Solar System means that their formation was mostly left undisturbed, unlike the chaotic and energetic inner Solar System. So any growing satellites were left in orbit around their primary, without being perturbed away from, or into, them.

This rationale does make sense. Either:

1. All the moons were captured satellites later on;

or,

2. they more or less started like this and captured the Nix's of this world.

I am beginning to think #2.

Triton probably is an exception. But then Neptune is of another size altogether.

Posted by: dvandorn Jul 18 2015, 04:39 AM

And, as usual, when playing with numbers, I got one wrong. Somehow I thought I had just read Pluto loses 5 tons of nitrogen an hour. I find I left off a couple of zeroes, it's 500 tons an hour.

So, I believe that makes the amount of nitrogen lost closer to 16.33 quadrillion tons over four billion years, and that's more like (if I'm figuring the scientific notation right, that was always hard for me to think in) 1.25e-3 percent of Pluto's present mass. More, but still a pretty small percentage. Nothing like the half of a percent that was estimated as little as ten years ago by those who anticipated a lot of gas loss from our favorite little KBO.

-the other Doug

Posted by: MarsInMyLifetime Jul 18 2015, 06:43 AM

Some years ago, part of the concern for mounting a near-term mission for Pluto was to intercept it before the atmosphere would freeze due to growing distance from the Sun, allegedly shutting down most cycles for the aphelion phase. I have not heard that concern mentioned for awhile, and had quietly reasoned that the concern was resolved with the timely launch of New Horizons. Yet I wonder whether the approaching aphelion season might indeed slow down the energy available for causing nitrogen loss. Thoughts on seasonal influence on gas loss (and how that affects projections about the planet's mass loss)?

Posted by: climber Jul 18 2015, 07:00 AM

A bit hard to read and understand all points here. A simple question and sorry if it has been addressed. Is the Heart facing the opposite direction of Charon? If yes, can it helps explaining all CO is concentrated there? Thanks

Posted by: squirreltape Jul 18 2015, 11:01 AM

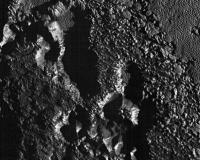

At this very early stage in the data release I can't help but speculate about the lineations outlining the 'polygonal' terrain in yesterdays release (17 July). After Habukaz showed us the 'troughs' look like they have ridge-like structure, I was immediately reminded of Enceladus' Tiger Stripes in appearance. But, if the polygonal terrain is due in part to convective cells, then the edges with the troughs should be subducting, rather than venting.

If the edges of the polygons are subdudcting, could the darker, lumpy, blocky material that is associated with the troughs in many places be some kind of bouyant flotsam that has been transported and gathered in these ridges? It seems very strange that the polygon edges have what appears to be so much blocky material in them but not in the polygons proper. The Hi-rez imagery of this and so much more should clarify just what exactly is happenning in these areas.

Posted by: Fran Ontanaya Jul 18 2015, 11:36 AM

Couldn't the simplest explanation for CO ice be that it's the area with the highest albedo? The difference between continuous airless insolation on a white surface and a black surface could be big.

Posted by: Sherbert Jul 18 2015, 12:12 PM

Remember that the area is getting the most insolation it will get during the northern summer. Yes, it gets more direct sunlight when the sun is high over the equator, but only for half a Plutonian day, so overall right now, even at a lower angle of incidence, it's getting insolation continuously. So it's not exactly a cold sink.

Good idea that, maybe the subsurface "aquifer" of CO was penetrated by an impact and the pressure release, belched out a fluid slush of mainly CO. The breach would be sealed over with a "scab" of frozen CO. The raised, brighter, heart of the Tombaugh region comes to mind. An object about the size of the one that knocked out the dinosaurs, might do the trick.

EDIT:- Strangely enough that was about a once in a hundred million year event, the rough boundary mentioned for the timeframe of the most recent activity on Pluto.

Looking at DLD's second, enhanced colour image, the distribution of material across the top of the icecap "land bridge" suggests a west to east flow to the equatorial winds here. It looks like material has been blown out of the dark Whale region up onto the icecap. It appears to be quite sharply bounded on the Northern edge, only small amounts of material have reached the areas of the pits and even less reaching further North to the Sputnik Plain. Prevented by the prevailing North to South atmospheric flow, presumably. There is not enough detail in the Colour map to try and spot turbulence at the boundaries of these gas flow patterns, reflected in the surface colouring. Might be something to look out for in the Hi Res images.

The coloured area, the cone of the ice cream, appears to be considerably lower than Sputnik Plain. The slope between them is seen mainly as the pitted terrain. The pits, almost certainly sublimation features, seem to form on slopes, in roughly parallel rows, created by the different insolation of the slope as shadows move up and down the slope. Similar rows of pits can be seen at the tip of Tombaugh, referred to by JB I think as "nests". I think they look like golf bunkers, except they are considerably larger.

Posted by: alan Jul 18 2015, 03:57 PM

IIRC during yesterday's press conference it was estimated the Nitrogen loss from Pluto would amount to a layer of 1000 - 9000 ft over the age of the solar system.

Posted by: alan Jul 18 2015, 04:10 PM

1. All the moons were captured satellites later on;

or,

2. they more or less started like this and captured the Nix's of this world.

I am beginning to think #2.

Triton probably is an exception. But then Neptune is of another size altogether.

In the Kuiper belt satellites are common for the largest objects and for objects with low inclinations and eccentricities (called cold classical KBO's) From what I've read the largest objects have satellites because their gravity wells were large enough to retain material from collisions which formed satellites. Many of the satellites around the cold classicals are loosely bound which has is one piece of evidence that these objects formed at these locations rather than being scattered outward by Neptune. In simulations of collapsing clouds of solid particles two objects often form which may indicate that the cold classicals formed as binaries. As far as I know these simulations haven't yet been done for objects as large as Pluto.

Posted by: Sherbert Jul 18 2015, 10:04 PM

So what is different about the Tombaugh Region that Carbon Monoxide ice collects only there in large amounts. This image shows the approximately real orientations of Charon and Pluto, and how the icecap relates to Charon.

http://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/thumbnails/image/pluto-and-charon-01.jpg

The tidal bulge in Pluto's atmosphere is on top of the Tombaugh region, creating a circular higher pressure zone. Elsewhere on Pluto the atmospheric pressure and temperature may not allow Carbon Monoxide to crystallise out as a solid, it remains as a gas in the atmosphere or is lost to space.

This postulated static high pressure zone must surely have an affect on atmospheric flow from hot hemisphere to cold. Would the flow be forced around the outside or through it, or would the higher pressure mass of gas start to spin?. Would warmer saturated "air" on reaching the higher pressure, deposit the various volatiles around its edge in the order dictated by their triple/freezing points, starting with the least volatile? Higher amounts of Methane ice on the Northern edge might be indicative of this. It is by no means the only explanation for Methane ice in this location. The climate is already looking anything but stagnant.

Earth's liquid oceans are intimately linked via a phase transition to the transport of latent heat around the planet in combination with heat transport in ocean currents. There is a single phase transition on Pluto, solid to gas and heat is transported around Pluto through latent heat exchange during deposition and sublimation of ices. The ices are just frozen atmosphere. Although at a much slower rate, heat can still travel through the surface ice, by convection and conduction.

Posted by: John Broughton Jul 19 2015, 04:33 AM

It might not be a coincidence that Tombaugh Regio lies inside what l think is an impact basin roughly 800km wide.

Pluto is differentiated and likely to have layers of different volatiles at various depths. Here the impact penetrated deeper than anywhere else in the equatorial zone. Liquids filled the void, flowed south and carved a shoreline. Some of the nearby ropey terrain was eroded, leaving behind those craggy water-ice mountains surrounded by blocky debris. It's anyone's guess though, whether the surface CO deposits were laid down at that time or more recently.

Posted by: serpens Jul 19 2015, 05:09 AM

It is a little sad that speculations on Pluto have been banished to an extraneous chit chat designation as opposed to a separate thread in the New Horizons segment. Regardless of data many of the forthcoming papers on the Pluto system will be informed speculation given the lack of definitive facts. For example, when did the Pluto Charon system form?

If as seems highly likely, Charon accreted from debris following a major collision we can safely state that this accretion would have occurred outside the Roche limit (around 3500 km for Pluto). The distance between Charon and Pluto now is 19,640 km but because they are tidal locked conservation if angular momentum means that Charon was once much closer. As separation increased there would initially have been major tectonic stresses gradually decreasing. Given Charon's lesser density and the fact that as the smaller body it would have become tidal locked before Pluto, the effects of tidal stresses on the surfaces of the two bodies would have been significantly different. If Charon was still reasonably close to Pluto tidal locking would have resulted in a tidal bulge that would collapse as distance increased resulting in something resembling a mountain in a moat. The tidal bulge for Pluto should gradually decrease until Pluto was also tidal locked without a residual bulge. Could Charon have received an external stimulus that resulted in the residual bulge being off centre? Could the final tidal locking been a recent event with residual tidal heat in the interior of Pluto?

Posted by: Paolo Jul 19 2015, 07:53 AM

Mike Brown (aka @plutokiller) had a couple of interesting tweets yesterday on the subject of Pluto being geologically active:

Posted by: Explorer1 Jul 19 2015, 08:03 AM

How long after the Triton flyby did it take until images with the geysers came down? Data rates weren't that much better from Neptune in 1989, were they?

Posted by: squirreltape Jul 19 2015, 09:00 AM

That is interesting. The assumption I'm led to here is that in order to explain the lack of cratering that implies a youthful, geologically active surface, some other method is required, namely the redistribution of frosts / ices that is prominent enough to obscure the cratering-record. Add in the lower chances of collision in the E-K Belt and the much lower collision energy (1 to 2 kms-1) then maybe frosts would do it.

But what of the atmosphere loss over time implying continual (or sporadic, ongoing) re-supply? Or are we seeing the last gasps and thin veneer of a primordial reservoir, however unlikely the odds?

I wonder how the water-cooler conversations explain these issues and which choice between geologically active and non-geologically active pleases Occam the most?

Posted by: ZLD Jul 19 2015, 01:35 PM

This is an interesting idea and I think theres a few elements that could lend itself to supporting it. However, I think the biggest reason this can't be the case is the lack of cratering. If that size of impact occurred, I would highly expect a ring system to form and as it condensed back to the surface, there would be many many impact craters. This would also deposit mixed elements across the surface and would leave few uniform looking areas, especially as large as Tombaugh Regio.

Posted by: stevesliva Jul 19 2015, 03:14 PM

A palimpsest basin opposite the sub-Charon point is possible, given all that.

Posted by: Sherbert Jul 19 2015, 05:34 PM

If we consider the Tombaugh region is the result of an impact, possibly from a de-orbitting moon, the energy and pressure during the impact is going to convert vast amounts of frozen volatiles for a short period of time into slush, liquid and gas that flows out of the impact basin. How far they flow would depend on their viscosity and how quickly they refreeze. This differentiation in their distribution should show up in the Alice and Ralph data more explicitly, but the lower resolution false colour images already gives a good idea that this is the case. I have borrowed Bjorn's excellent map to illustrate (see post 902 of the main NH Near Encounter thread).

https://www.flickr.com/photos/124013840@N06/19805634236/in/dateposted-public/

The green circle is the outline of the proposed impact basin. It is pretty obvious.

The purple outline shows the area of serious surface deformation and resurfacing from the impact event and it's aftermath.

The red circles show possible impact craters, which could be from secondary ejecta impacts.

The yellow area is the approximate area of Carbon Monoxide already highlighted by the team.

The blue lines outline the areas where other volatiles liquified during the impact have flowed away from the crater. (Roughly the pale blue/cyan coloured parts of the false colour image.)

A de-orbiting moon should hit very near the equator, but the tidally locked Charon creates a slightly deeper gravity well above the centre of the green circle and so this would slightly change the velocity of the moon and drag it just slightly north of the equator. Others might know better, but this small influence would only occur very close to the surface of Pluto, causing the object to scrape a South to North furrow just before impact, the cone of the ice cream. I have no idea if this sort of intuitive scenario is actually plausible, but thats my two cents worth.

Although I tend to favour the moon or large mountain sized impactor, I don't rule out the impactor being Charon either, scraping past the surface. It could be that only Charon's tenuous atmosphere actually contacted the surface initially to create the furrow and then a tiny patch, a few square kilometres, of Charon's surface actually contacted Pluto at the impact site, where the super heated atmosphere and flash sublimated volatile ices, cushioned the impact and "bounced" Charon away from the surface significantly altering its trajectory. I still have difficulty in believing that Charon was then captured, but there may be a small set of solutions that allow it, so I am still keeping an open mind until we see more of Charon's North Pole.

Posted by: John Broughton Jul 20 2015, 03:53 AM

The curving scarps I circled would be the basin's outer rim. It is equivalent in size relative to Pluto that Mare Imbrium is to the Moon. Mare Imbrium also has an incomplete rim and no trace of inner rings, after being flooded with lava when the floor rebounded. Moderate-sized craters on Pluto can be made out despite having been blanketed under a kilometre or so of ice deposits, but there are none inside Tombaugh Regio. However, there appears to be craters west of that area that haven't been blanketed, particularly on the upper half of the whale's head. If Pluto ever had a thick atmosphere, there could be signs of its effects on the surface in high-resolution images of that region.

Posted by: serpens Jul 20 2015, 04:23 AM

'In current hallway conversations with planetary scientists most are unconvinced by the evidence that "Pluto is geologically active"'

Yes, I can see a lot of tectonic changes taking place before the system became tidal locked but once tidal energy dissipated the surface should have been stable. While just one possibility, the mountain in a moat does does seem akin to the remnant of a collapsed tidal bulge. One thing I had forgotten and was reminded of in an old Dobrovolskis paper on the Pluto Charon binary system was that tidal dissipation would also cause the equatorial planes of the two bodies to realign to the [edit] orbital plane. The tidal bulge would become static as distance between the bodies increased but probably well before Charon became completely tidal locked, So after collapse it would potentially be displaced from the equatorial plane - just like the mountain in a moat. Yeah sheer speculation on my part but probably less speculative than geological activity or impact to explain the strange topography of the mountain in a moat. The upper bounds of the time taken for tidal locking for the system seems to be in the region of 100 Mya so the tidal locking is not in any way an indication of extended age and associated expectation of extensive impact craters.

Posted by: Bill Harris Jul 20 2015, 05:55 AM

Sad, but anticipated.

Posted by: marsbug Jul 20 2015, 11:11 AM

I didn't quite follow that Serpens, do you mean that tidal locking could have occured within the last 100,000,000 years and so the surface was being reshaped within that time, hence the surface is stable now and yet relatively craterless? That would place the formation of the Pluto/Charon system relatively recently, would it not?

Posted by: Mongo Jul 20 2015, 12:46 PM

I don't see this. There are so many example of large moons (half of the top ten KBOs by diameter have at least one) that for them all to be the result of a rare giant collision event is extremely unlikely. It's far more likely that large moons are a natural result of the KBO formation process in the low-energy environment of the outer Solar System, with each large KBO the "primary" of its own planetary accretion disc, from which large moons form in situ. Given the great distance from the Sun and the low planetisimal density, it seems likely that many of these KBO accretion discs would remain undisrupted until the large moons have coalesced (about half the time, going by the observed statistics).

Posted by: serpens Jul 20 2015, 01:47 PM

All I am saying Marsbug is that if the Pluto - Charon binary system formed following an impact then the time from impact to tidal locking in the current configuration would have taken a comparatively short time in relation to the age of the solar system. When such formation occurred is an unknown but most of the surface features seen could readily be attributed to tidal and rotational deceleration tectonic processes and the lack of cratering does imply a reasonably short time since tectonics/resurfacing and dissipation of tidal heat. It actually doesn't matter whether formation of the system was due to impact or simultaneous accretion. The same roche limit, conservation of angular momentum considerations would apply.

Posted by: marsbug Jul 20 2015, 02:02 PM

Thanks mate, that's clearer. I agree.

Posted by: Bill Harris Jul 20 2015, 05:43 PM

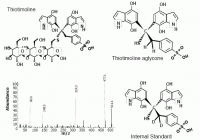

Actually all of this is quite evident when you consider that the equatorial ice-field of Tombaugh Regio is an admixuture of variously CO2, CO, CH4, N2 or Ne and the organic refractory compound thiotimoline, which was likely introduced into the Pluto-Charon system by a passing Kuiper belt Chronoid body during the last age of Aquarius. By adding even trace amounts of thiotimoline to silicate minerals and refractory organics entrained in the gas flow, plus any desublimated dihydrogen monoxide also entrained.it allows workarounds around the various laws of Geology such as Uniformitarianism, Superposition and Superimposition. This get around some problems in the explanation of how younger strata can be emplaced below older strata. But since the exact properties of thiotimoline are not well-known under the conditions near this disputed planetary system, especially at the always-in-darkness cold trap in the South polar region, the actual effects on the geochron timeline is not well-constrained.

An idea of what could be found can be gained by reading "The Endochronic Properties of Resublimated Thiotimoline", I.Y. Ozimov, 1948, Campbell Press, with recent supplemantal material in http://danm.ucsc.edu/~phoenix/danm203/thiotimoline.pdf

Remember, there are no catastrophic processes, only catastrophic events. Sometimes things just go http://jersey.uoregon.edu/~mstrick/geology/geoFantasy_page.html.

--Bill

Posted by: mchan Jul 20 2015, 09:38 PM

![]()

I, for one, would welcome a point-by-point rebuttal of the earlier posts within forum rule 2.1.

Posted by: serpens Jul 20 2015, 10:49 PM

Hardly seems worthwhile mchan. Best to ignore the science fiction/fantasy world of Isaac Asimov's thiotimoline.

Posted by: serpens Jul 21 2015, 06:03 AM

Following up on Dobrovolskis' paper led me to a collection of papers from various authors, speculating on the Pluto-Charon binary system. It was compiled by Alan Stern and published by the University of Arizona in 1997, simply titled Pluto and Charon. While dated the papers remain relevant and make fascinating reading. Some extracts are in Google books. Well worth the search for anyone interested.

Posted by: Sherbert Jul 22 2015, 05:19 PM

--Bill

Bill, you old rascal, excellent post.

Posted by: Bill Harris Jul 22 2015, 09:48 PM

![]()

Posted by: JRehling Jul 23 2015, 08:36 PM

I've inadvertently stolen this thinking in musings on the Pluto Near Flyby thread.

To develop it out a bit, there is a state of solid CO that packs a tremendous amount of physical energy when under pressure, and releases it explosively when the pressure is removed. The required pressure could only form very deep inside Pluto, but perhaps this condition was met. Then, a relaxation in the pressure could trigger a single, colossal explosion.

An impact might be the trigger. We also know that Pluto is venting stuff anyway, so maybe the integrity of the material that was providing the pressure crossed a threshold.

If any of this is true, one would expect it to happen, perhaps, only once in Pluto's history, so to have it happen very recently would be improbable, but not impossible.

Posted by: Bill Harris Jul 23 2015, 11:47 PM

I don't think it's inadvertently stolen, but I do like your line of reasoning on the CO / CO2 energy release of the phase change.

On the other hand, it would be improbable for a one-time event to have happened so recently as the lack of craters implies, so perhaps its something somewhat less extreme but periodic that vents from Tombaugh Regio. Still, while a single event happening recently is improbable, it's not impossible. It would be nice to know the cratering rate in Pluto's neighborhood, to say the least.

Polycarbonyl

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polycarbonyl

--Bill

And add to this molecular gas ices and hydrocarbon ices and water clathrates all under alien conditions...

--Bill

Posted by: Sherbert Jul 24 2015, 07:02 AM

I'm just glad to see others are thinking similarly. I did not know about that phase change. As Bill says the other super volatiles are going to have their different influences. The Tombaugh region is mainly about CO, but the majority of Pluto is about Nitrogen and Methane. It is perhaps unfortunate that the NH close flyby is over this "aberration" on Pluto's surface. The images from North and East of Tombaugh will hopefully tell us more about pre impact Pluto, which one suspects is a lot more sedate.

The Cthulhu region near the impact area has steep cliffs, but away from there the sides of the basin appear a far more gentle slope. I'm thinking the depression is more an illusion created by mountainous terrain to the North and South of the equator. It may be at a similar level to the plains of the "temperate latitudes". Flows of Pluto's atmosphere travelling from "warm" to "cold" are going to travel to points where the vapour pressure and temperature conditions mean the gases, Nitrogen and Methane mainly, are going to freeze and collect. The axial tilt obviously messes with this simplified scenario, the predominant flow appears to be North to South. The "Ropey" mountains are in my eyes the Northern extent of the Southern mountains. This flow has definitely helped to spread Carbon Monoxide from the impact site, South, over the Sputnik Plain and on down towards the equator. Both aeolian transport and sublimation/deposition seem likely to be involved, modifying the initial overflow from the impact basin at the time of the impact, to create the current landscape.

Posted by: xflare Jul 24 2015, 04:54 PM

I think the heart, at least the left side, is a vast cryovolcanic lava flow.

Posted by: Gladstoner Jul 24 2015, 10:12 PM

West Tombaugh Regio does appear more like a caldera with a lava lake than (what I think of as) a glacier.

Posted by: marsbug Jul 25 2015, 03:48 PM

Looking at the images of the 'nitrogen glaciers', I'm reminded that the solubility of water ice in liquid nitrogen is unexpectedly high:

http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4613-9865-3_113

https://inis.iaea.org/search/search.aspx?orig_q=RN:16033601

given how ell these glaciers seem to flow, is a liquid component in microveins within the bulk ice a possibility I wonder, and has it been slowly eating its way into the water ice 'bedrock'? That would make the whole system a very interesting experiment into a large scale physical and chemical system the likes of which we simply could not do on earth.

Posted by: Rittmann Jul 25 2015, 05:54 PM

Looking at the images I've come to some ideas that, so far, I have not seen from anyone. Since they are essentially speculative, I'll put them in this thread and not in the encounter thread.

1.- Equatorial dark band

Looking at the surface of Pluto and its crater distribution so far, I am under the impression that cratering is essentially on the equator. We can see in the maps that resurfacing has happened in the northern latituted, and Tombaugh region is very young, but the Cthulhu region has several craters, some of them filled with the dark element.

One of the first ideas that came to my mind was the possibility of a collapsed ring system around the equator. Before the encounter it had been commented that the Pluto system could feature a transient ring system created from dust from its moons. In the turbulent gravity environment of Pluto, with the barycenter far from the planet surface and Charon's pull affecting assymetrically the space around pluto, I speculate that instead of a ring system, dust would rain towards the planet's surface and collapse around the equator. Tidal locking with Charon would have affected the deposition over time, making two differentiate patterns. Craters would then have higher chances to happen around the equator if they were fragments of the original event that created the current system's configuration, and as time went by, would have rained down on Pluto's equator along the dark dust. Charon's influence would have prevented a slim ring to form, raining over a range of equatorial latitudes instead.

This idea has its own weak points. It doesn't explain Charon's dark pole - there should also be an equatorial belt in the moon -. It also doesn't explain why there appear to be dark materials on the peaks of some mountains.

In this scenario the original impact that created the double planet would have caused full resurfacing of Pluto and Charon, and over time Pluto would have received the rain of dust over its surface, along with some debris.

2.- Energy source for Pluto's current resurfacing

A global scale resurfacing event is likely to have happened in the event that created the Pluto / Charon system, if as it seems, it was created by an impact.

Pluto's mass is (1.305±0.007)×10^22 kg. It currently loses 500 metric tonnes of material every hour according to the data. Assuming a constant rate - which is a lot of assuming, since I believe Tombaugh is currently the biggest source for mass loss in the planet due to its young volatile exposed ices, in contrast with the older areas - we have the following numbers:

4.38*10^9 kg /year

1.971*10^19 kg in 4.5 billion years

We are three orders of magnitud below the whole planet's mass here, but this mass was originally only on the surface. Pluto's surface area is 1.77×10^7 km2, so on the current surface of Pluto could have lost over the life span of the Solar System 1.110 metric tonnes of mass per square meter.

Considering that the possibility for sub-surface liquid masses has been estimated in the scale of meters, makes me propose the following hypothesis: as surface mass is lost, underground liquid masses are able to expand due to the release of pressure. These masses could, in some places, crack causing faults - ices tend to be brittle - releasing on the surface as they expanded against the almost void of the surface of the planet.

In the areas where this first happened the process would speed up since the exposed clean ices from the underground lakes would sublimate at a higher pace than older, more stable surfaces. This would release faster enough pressure for even more underground deposits to burst into the surface, including water deposits.

According to this idea, Tombaugh region would have been the place where the liquid underground sources would have been nearest to the surface - it is more or less the exact anti-Charon area, so that could have influence through tidal heating in the past -. Once enough surface ices sublimated into the atmosphere and space, the pressure release would have caused the first nitrogen and CO underground sources to burst, flooding the surface and speeding up the process. As the process sped up, deeper sources with liquid water would have also bursted, causing the ice mountains to show up over the nitrogen and CO plains.

In the first hi-res image we can see several faults across older surface south of Tombaugh, but none of the faults seems to be affecting any mountain in the area.

Furthermore, this would explain the shorelines since the plains' surface would have sublimated over time, leaving the original terminators of the expansion process - still made of materials that don't as easily sublimate - to remain.

PD. My first post in this fantastic forum!

Posted by: ZLD Jul 25 2015, 08:42 PM

Just to throw an idea out thats been rattling around in my head for the past week, with regard to the Tombaugh Regio area, I don't believe it is or was a an impact. Looking around the rim, there are areas that would allude to it being crater like but if there is tectonic activity, it could possibly form much of what is visible as well, more on this in a bit.

Let's back up a little. In 1989, Pluto was at perihelion and conditions were most favorable for the densest possible atmosphere from seasonal change. In the time since, the surface pressure appeared to be increasing until a rapid falloff observed by REX. During yesterday's science update, they didn't appear to have the data from the SOPHIA occulation observation. So we can't rule out the possibility that there could be error in the way atmospheric pressure is calculated during a distant occultation, or there could be an error in reading the REX data, or some other unforeseen error elsewhere. However, lets continue to assume everything is correct and accurate. This leaves the question as to why pressure would increase and suddenly fall off, especially with the abundant and constant release of nitrogen that is escaping.

Back to Tombaugh Regio. Blatantly, I feel the area is currently and has been a sea for a very long time, possibly composed of nitrogen. There well established areas that look like shorelines, theres what appears to be migration through the region, lack of any visible impact craters and very strange linear or polygonal features that overlay the region. During an earlier press briefing, an idea that this looked like a boiling liquid really piqued my interest.

A large assumption to suggest but if Pluto had a slightly denser than measured atmosphere during perihelion then this nitrogen sea may have been liquid at the surface, maybe even for just a few years. Then as Pluto began to cool off again, the atmosphere began to refreeze, decreasing pressure to a point where the nitrogen sea began to boil and eventually settled with a relatively thin membrane over the still liquid sea. As this action was occurring, it could have possibly thrown off atmospheric measurements as the nitrogen was boiling away and escaping into space. A large amount of nitrogen still escapes the body, possibly through the linear features in the region as well.

Back to tectonics. This is really out there but looking over the wonderful maps by scalbers, the area previously referred to as the 'train tracks' looks like it shares some similarities to Tombaugh Regio. I mentioned a while back from my versions of the stacked approach data, that it seemed like Cthulu possibly sat slightly above the mean terrain. I still personally see that in some regard with the higher resolution images. These dark areas may be a sort of continental plate and the bright areas like Tombaugh Regio more like a sea floor plate. The biggest contributor to this idea is the segment of the surface, running along the west side of TR. It appears very strikingly like a rift valley forming, and not simply ice burgs breaking away. If the previous maps of Pluto are at all accurate (they seem to be), then there is likely even more of the bright areas in the south that make up these sea plates. This further lends to why the dark regions would appear to be heavily bombarded relative to TR. As for the northern ice covered terrain, there appears to be a difference in types and maybe numbers of cratering between the areas just north of TR and just north of Cthulu. This could indicate that under this ice sheet is a continuation of these differing plates, softening craters over the less viscous areas.

Posted by: scalbers Jul 25 2015, 10:33 PM

Welcome to the forum Rittman. I would like to check if your numbers come out better using the mass loss value I recall hearing, of 500 tons per hour?

Posted by: Rittmann Jul 26 2015, 09:53 AM

Whoops! True. I've edited the post to match things. But this means that Pluto, assuming a constant loss rate from its birth - which is a lot of assuming - has lost 1/500th of its mass due to this process.

1.110 tonnes per square meter, if we use the density of N2 ice at Pluto's temperature as 1.35g/cm3, means a column of approximately 1500 meters per square meter. That is a lot!

My conjecture, though, is that the current escape rate is working at a far faster pace due to Tombaugh region's popping up having happened relatively in recent times - 100MY, for example -. Older, "baked" areas like the equatorial dark belt would have practically stopped sublimating elements since the dark material coating the terrain would act as some kind of protection - thus, the apparent surface is also older since this mechanism would have no power to resurface the area.

But if we account Tombaugh as the main area where sublimation is happening, and the event that bursted the current ices over its plains as 100MY old, then we can formulate a rough approximation:

1.- Tombaugh's exposed ices, even if it is a reduced region through Pluto, account for, let's say, 25% contribution to the overall mass loss.

2.- This increased rate has happened only during the last 100MY.

3.- I don't have the total surface area of Tombaugh regio. I will assume an approximate shape of a circle and an approximate diameter of 1200km. This gives a rough total area of 1.13*10^6 km2

So, 125 metric tonnes per hour from Tombaugh regio for 100MY gives:

1.- Mass loss: 1.095*10^17 kg during 100MY

2.- 97 metric tons per square meter of mass loss

This gives a total loss of approximately 77 meters of mass loss over the surface during 100 MY.

Considering that some think that the liquid layer for Pluto's characteristics may be just a few dozen meters below the surface, we may have here a plausible mechanism for the surface renewal. Add to this that the figures are all very rough, so a surface 200MY old would give 150 meters of mass loss, carving the shorelines we see. Or Tombaugh regio could account for far more mass loss than just 25% since it is not "baked", speeding up the process.

Why this area? If the wobbling we see by the moon tides on Earth is any reference, Tombaugh regio being anti Charon would be one of the highest original elevation areas in Pluto, or at least one that would have been the most active during the tidal locking with the moon, providing a source of energy over a long time during Pluto's history, and creating a concentration of pools near the surface.

All in all, here is my speculation for a mechanism for resurfacing of the planet.

Posted by: Bill Harris Jul 26 2015, 10:23 AM

Not bad First Posts and welcome, Rittman. The Pluto-Charon system is an amazing world and with new (and improved) images arriving almost daily our knowledge of the system is evolving at that rate. These are wonderful times.

I am working up a "Poster Session" on the geomorphology of Pluto. This is, of course, presently a work-in-progress, and the initial Index image is at:

https://univ.smugmug.com/New-Horizons-Mission/PlutoCharon/

--Bill

Posted by: Bill Harris Jul 26 2015, 10:44 AM

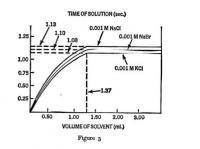

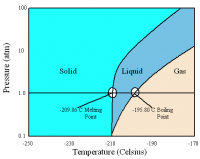

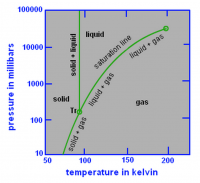

Yes. And look at the phase diagrams for Nitrogen and Methane that I have seen posted here-- the triple point is attainable at reasonable temperatures and pressures. And that is not even considering the properties of admixtures of Nitrogen with other gases such as CH4, NH4, CO, CO2. Nor the properties of clathrates with the forms of water ice.

I am by no means a cryochemist/physicist so all this is mind-boggling to me.

--Bill

Posted by: dvandorn Jul 26 2015, 02:45 PM

Also, I've not seen this mentioned specifically, perhaps the weight of the equatorial ice cap that is Tombaugh Regio is compressing the underlying water ice crust and causing the tectonic cracking we see around the region. Specifically, I'm thinking this could be the mechanism that created the radial cracks coming away from the region and extending into the Cthulu region.

That would make as much or more sense to me as the radial cracking being caused by an impact. Other basin-like impacts into icy worlds, like Callisto, for example, generate cracking in concentric rings around the impact point. These are cracks extending outward radially from the center of what appears to be a gigantic pile of nitrogen ice covered by a layer of CO ice. The weight of that pile could be what's deforming the surrounding terrain and causing the radial cracking.

-the other Doug

Posted by: MarsInMyLifetime Jul 26 2015, 03:47 PM

Several interesting things jumped out to me following this past week's briefing:

First, the Eastern contact of the convection zone against the weathered terrain looks remarkably straight, and I can no longer reconcile its shape with a presumed border of an impact crater--I think that other hypotheses are now called for. Clearly the big story is about the apparent convective upwelling of ductile nitrogen ice. The relatively straight contact zone suggests an interaction of that zone with something about the "bedrock" itself such as a fault or more durable composition.

Second, the image of presumed glacier-like activity presented yesterday shows some fractures in the weathered surface parallel with the contact zone (not the radial lines mentioned before). Rather than the soft ice encroaching over the weathered surface like lava, I have the mental image of crust being subducted underneath the active flow region of the convection cells, and being fractured by the stress of the downward dive at the edge.

So my latest line of thought, trying to align with the obvious convection activity, is to view the region as a slow but voracious geologic hotspot, a material reprocessing factory that is gnawing its way northward through the older plate, leaving a trail of various after-effects to the south and east. This still does not explain carbon monixide production that wells back up in the Sputnik Planum surface; the most obvious thing I can imagine is that the carbon monoxide, in a much earlier history, was differentiated as a layer that the hotspot is now upwelling through.

Posted by: hendric Jul 27 2015, 06:03 PM

Will Ralph give us direct temperature measurements from the surface? Based on the descriptions I read, we only get indirect temps based on presence of N2, H2O, and CO.

Even with the JWST, it looks like we won't have enough resolution to monitor regional temp changes on Pluto, other than at the Earth-facing hemisphere level (JWST is .1", Pluto's angular size is about .1" as well.)

If Tombaugh Regio really is shrinking vs Hubble pics, then those margins between the ice and the hills have to be pretty dynamic to show a change in so "short" a time - especially since the change looks geologic and not just a veneer sublimating away.I am really very confused as to Sputnik Planum's temperature relative to the surrounding areas. My gut say the center must be warmer, to cause the overturning and CO release, but being as white as it is, my brain says it must be colder. Maybe a temperature reading across Sputnik Planum looks like a crater cross section, with warm edges from the darker Cthulhu, a warm center from a Hawaii-esque hot spot, and a ring of colder plains. I think the whitest area in the center probably stays year-round on Pluto, with the light gray and darker gray portions extending out during the night time growth stage - collecting debris from underneath, and melting/sublimating back during the daytime shrinking stage.

Another possibility is TR has no heat source, but is a thicker section of ice that survives the summer, acting as a seed (or more likely several seeds) for the winter expansion. One weird effect we don't get to see much on Earth anymore would be the glaciers growing up-valley vs down-valley. This is caused by the ice starting growth at the colder shaded bottoms of craters/valleys, spotty across the landscape, vs collecting at the top of cold peaks as on Earth due to precipitation. As it expands, the initial layers are put down directly without flow at the margins, and once it gets thick enough, probably at the center or in very shaded valleys, it starts flowing outwards. This would help explain the dichotomy of light grey & dark grey. The light grey happens during the initial layers phase, with material picked up as the layer grows mostly vertical - there would be less darker material the higher up the valley it goes and so when they meet the ridges show up whiter that the rest. This would help to explain the isolated mounts with grey areas and white spokes, like in NW SP. The central white area is where it all started, and enough ice has grown there to push out all the grey.

But as it gets thick enough to start flowing, then it switches modes to gather the darker grey material at the edges via flow. This would cause the dark grey material to thicken into a black line once two neighboring glaciers connect over a ridge. This effect would be most noticeable where there is a slow elevation change, explaining the NE area of SP having the most of these. A shallow rise with ridges allow for most of the darker material to stay close to where it started and meet up with material from the other side of the ridge. Some hand-waving might necessary when the glacier gets high enough that it tumbles over a ridge that doesn't have another glacier on the other side, but there are a few candidate features to the SE.

Darker material collecting above/along the ridges where two glaciers meet could also cause the fractures/trenches - as more ice collected in the cold center of the glacier, the darker material causes the trenches via melt, eventually melting deep enough that the overturning ice above it covers it up, leaving a remainder line.

In the summer, the dark material starts near the top of the ridges because of the effect above, but as it progresses falls down the valley sides, allowing the cycle to repeat.

This second idea fails on explaining the source of CO. Perhaps the ice sheet is thick enough in the center that the bottom heats CO and it can escape via the weak spots made by the dark material at the margins of the cells. It does explain the cells though as the seed cores of the glaciers that started growth in the winter. With them being white it would tend to self-reinforce the growth, potentially continuing well into summer or even year-round.

Posted by: JRehling Jul 27 2015, 07:31 PM

Before this month, the observed changes in Pluto were always inferred to be "weather" related, because Pluto was assumed to be geologically dead. Now, however, it's open to speculation if any of the changes that we've observed over the decades were weather-related as opposed to the aftermath of geological events. We haven't watched it long enough to tell the difference. (Indeed, we would have to have records going back to about William the Conqueror's time to be sure.)

Pluto's orbital period is still short compared to many geological timescales (e.g., major impacts), but it may not be short compared to the frequency of some kinds of endogenous activity. Imagine, a world with non-zero weather where weather might be slower than geology.

Posted by: hendric Jul 27 2015, 08:21 PM

Good point, the "shrinking" of TR could be caused by the overturning slowing down as Pluto leaves summer, letting more of the tholins stay on the surface on the cells as they slow down and stop.

Posted by: Bill Harris Aug 2 2015, 01:54 AM

With the 250-year year plus the orbital eccentricity plus the axial tilt, Pluto is bound to have significant seasonal variability. We'll need to monitor it for a while...

--Bill

Posted by: HSchirmer Aug 9 2015, 04:19 PM

So my latest line of thought, trying to align with the obvious convection activity, is to view the region as a slow but voracious geologic hotspot, a material reprocessing factory that is gnawing its way northward through the older plate, leaving a trail of various after-effects to the south and east. This still does not explain carbon monixide production that wells back up in the Sputnik Planum surface; the most obvious thing I can imagine is that the carbon monoxide, in a much earlier history, was differentiated as a layer that the hotspot is now upwelling through.

Perhaps you are seeing cracks from glacial rebound, as the sunlit edge of Tombaugh recedes and is reistributed "south" and "east" in those "snowdrift" bands?

Consider a planet where "atmospheric pressure" could also mean the pressure exerted by a collapsing atomsphere freezing out as a slab.

The atmosphere itself IS the meteorological cycle of precipitation.

With an elliptical orbit, IIRC P&C at closest (circa 1990) get 2.8 times the illumination and heat than at farthest in 1880s;

With axial tilt, 1990's closest approach and 1880s fathest are both during equinox, you get "rotisserie mode" where the entire planet is exposed to sunlight.

We are seeing the planet as it moves towards solstice, or "broiler mode" where the total amount of solar flux is less, but it is concentrated

on only one hemisphere.

I also wonder whether this could be a glacial cold-trap, a growing pile of condensed atmosphere with a covering of CO hoarfrost or ice-spire "pennitents"

I wonder whether this might be a CO "deccan traps", an ice flood that has erupted from below.

We're not sure whether flood basalts on earth are a result of a focused plume of geologic heat or an impact or both.

If Tombaugh is antipodal to Charon, you might have some sort of tidal stress connection, rather like enceladus tiger stripes.

Posted by: HSchirmer Aug 26 2015, 05:00 PM

Penetration by an impactor of a layer of Carbon Monoxide ice, or a postulated liquid CO "aquifer", below the surface, leading to an explosive release of pressure, liquid and gas, subsurface and surface volatile ices liquifying add to this to fill and overflow the crater. In addition, what look like once "molten" crater walls, possible "splash" zones, a plausible impact basin and strong evidence of fluid flow covering older surfaces, all seem to me to fit such a scenario. Elsewhere in the Solar System, such large resurfacing events are frequently the result of impacts.

One might hypothesise that "solid" material, such as Water ice, possibly in the impactor, caught up in such an "explosive decompression" combined with massive volumes of rapidly expanding gas, could be ejected and then deposited in the surrounding area as "rubble piles" or "mountains". I find it difficult to conceive that the amount of energy required to create the Norgay and Hillary mountains could be generated this way, but it is a big crater, the pressure at such depths must be considerable, the gravity low and the energy of the impactor huge. Those with the appropriate models and data might be able to say one way or the other. A possible explanation, but I have to concede, one that seems unlikely.

More conceivable, is the possibility that "bedrock" Water ice intrusions have been exposed due to erosion by the "warm" fluid overflow from the crater. In places it does seem the fluid flow has left a sharp "shoreline" and "melted" valleys into higher terrain, but I'm not convinced its an explanation for the Water ice mountains. It still requires some tectonic or geothermal explanation for the Water ice intrusions being there originally and an awful lot of erosion.

Hopefully with more data, will come enlightenment.

Very interesting hypothesis- I've shifted my reply to the speculation thread.

Tomabugh as an impact feature is what I first thought. It looks like an impact basin. The ice mountains look like icebergs in a frozen sea.

However, I think Tombaugh is not an impact feature.

I think Tombaugh is the remnant core of pluto's ice cap, caught mid-way as it glaciates its way from north pole to south pole.

I suspect that Tombaugh looks "new" because if a sizable portion of pluto's atmosphere froze out in the last few months/ years,

it had to go somewhere, and the most likely place for a freezing atmosphre to go is to freeze onto existing ices.

After a bit of thought; after a bit of reading on N2 ices and plutonian seasons; it appears that pluto's ice cap should move from pole to pole.

I think we are seeing an ice cap where the northern rim is receding because the northern hemisphere's days now lasts for weeks, then months, then years, then decades.

I think Tombaugh's northern rim resembles a crater because the sublimating ice leaves a depression, rather like the north american great lakes.

As the southern latitudes cool down, night begins to last weeks or months, soon years and decades, and frost begins to covern the southern hemisphere.

Perhaps Tombaugh will be redistributed as a broad, thin, south polar frost cap.

Posted by: HSchirmer Sep 23 2015, 09:05 PM

http://www.unmannedspaceflight.com/index.php?showtopic=8071&view=findpost&p=226644

In fact, we're going to be releasing some images later this week of a completely unique type of terrain

-- it's just mind-blowing and makes my head hurt to think about how it may have formed

-- that we see on Pluto that we don't see anywhere else in the Solar System.

So, anybody willing to speculate about what they found?

I'm kinda leaning towards fields of giant crystals, sort of superman's fortress of solitude or 1970s YES album cover art.

Posted by: ZLD Sep 23 2015, 10:14 PM

Could be but that isn't exactly something we've never seen. I'm going to guess it probably has something more to do with some type of terrain that requires more energy than would be expected at Pluto. That seems to be a really common trend. Or a big 'Welcome to Pluto' banner, in large print English.

Posted by: HSchirmer Sep 25 2015, 02:00 AM

Moved

Posted by: HSchirmer Sep 25 2015, 02:12 AM

Moved

Posted by: Nafnlaus Sep 26 2015, 12:36 PM

If it's from precipitation then one has to go back to the question of, "where is Pluto's nitrogen coming from", since it's lost vast amounts over geological timescales. I can't picture any other possibility other than that Sputnik is the source, not a sink - akin to the "lava lake" hypothesis mentioned above. Plus, note how the thickest "precipitation" (or more probable, direct condensation) appears to be on the terrain directly adjacent to Sputnik (including glaciers that flow back into it) - also suggesting Sputnik as the source. Lastly, pretty much everyone (including the team) seems to be in agreement now that Sputnik is a low point, not a high point. Glaciers formed by precipitation build high points, not low points. Yet the surrounding terrain flows into Sputnik, not out of it. And there's sizeable shoreline cliffs around it.

As to why it's where it is... it's directly opposite from Charon. Surely that's not a coincidence. While I don't exactly have a planetary model onhand, I wouldn't be surprised if the interplay of forces pulled the water-ice crust into a thicker layer on Charon's near side, exposing a nitrogen-ice "mantle" on the far side (Sputnik)

Posted by: HSchirmer Sep 26 2015, 04:41 PM

since it's lost vast amounts over geological timescales.

Well, as I understand it, we are seeing it loose vast amounts now, assuming that's the steady state condition, and then extrapolating backwards and forwards. It could be that the recent perihelion equinox (closest approach and "rotisserie mode" which illuminates the entire planet, triggers a one-an-orbit spike, which raises atmospheric pressure quickly, and triggers the loss.

I would associate a source with a big pile of stuff, perhaps with a little depression on top.

Something closer to olympus mons or kllauea (point) or mid ocean ridges for linear features.

Well, a source of sublimation doesn't have to be the source of the material, it could be the source of the heat differential that moves the material. So, on earth thunderstorms aren't the source of the water that rains down, they are a manifestation of the heat transfer that moves the water around.

Well, earth glaciers flow into depressions. Pluto just finished several decades of rotisserie scorching, it's possible that we are seeing the glacier rebuild.

While I don't exactly have a planetary model onhand, I wouldn't be surprised if the interplay of forces pulled the water-ice crust into a thicker layer on Charon's near side, exposing a nitrogen-ice "mantle" on the far side (Sputnik)

Could be lots of things - a barycenter effect where less dense material accumulates on the farside from pluto, the inverse of the Moon's dark seas facing earth.

Could be a tiny difference in light reflected from Charon, I've read that N2 ice is extremely sensitive to temperature, a 1 K increase causes a 100% increase in pressure, so if Charonshine raises that hemisphere's temperature by .025 of a K, that's a 2.5% difference in pressure. A 2.5% difference in pressure is a strong high pressure system on earth, enough to push air to other areas.

Could be that tidal effects create a static air tides that hovers over Sputnik and favors deposition there.

Weather on earth circulates and "desert bands" and "rain bands", could be that Sputnik represents a "tropical rain spot" in the circulation pattern.

Posted by: Charles Astro Sep 26 2015, 06:19 PM

One possible trigger for the formation of Sputnik Planum could have been an impact at a location where Pluto's crust happened to be relatively thin. Some areas of Pluto do have quite big craters. The crust must be thicker there.

http://charlesastro.wordpress.com

How Sputnik Planum could have grown from a relatively small impact crater to it's present size.

http://charlesastro.wordpress.com/2015/08/31/ice-tsunamis-due-to-plutos-thin-crust-sinking-temporarily

Judging by the slabs deposited in al-Idrisi Montes the thickness of Sputnik Planum's previous crust has turned out to be ~5 km, rather than the ~1 km guess-timate in the schematic.

Rather than an impact, the crust under Sputnik Planum might have cracked up through entirely internal geological processes due to a slow build up of heat under an insulating crust. This would be something like the scenario that has been proposed for Venus, where large sections of its crust get recycled in massive episodes of volcanism after a long periods of relative quiescence during which internal heat builds up. Because it doesn't need a lucky impact this sort of slow cycle scenario might be a more plausible explanation for Pluto's activity.

Posted by: Nafnlaus Sep 27 2015, 07:02 PM

Judging by the slabs deposited in al-Idrisi Montes the thickness of Sputnik Planum's previous crust has turned out to be ~5 km, rather than the ~1 km guess-timate in the schematic.

Rather than an impact, the crust under Sputnik Planum might have cracked up through entirely internal geological processes due to a slow build up of heat under an insulating crust. This would be something like the scenario that has been proposed for Venus, where large sections of its crust get recycled in massive episodes of volcanism after a long periods of relative quiescence during which internal heat builds up. Because it doesn't need a lucky impact this sort of slow cycle scenario might be a more plausible explanation for Pluto's activity.

Do you think it's just a coincidence that Sputnik is exactly opposite Charon?

Posted by: JRehling Sep 27 2015, 07:38 PM

The Moon settled into a tidally locked orientation where the thinnest crust was exactly opposite the Earth; consequently, the overwhelming majority of maria are on the Earth-facing side, clustered around the sub-Earth point. As I understand it, this could equally well have turned out the opposite, with the thinnest crust centered at the anti-Earth point, for reasons similar to those why we have two high tides each day on Earth, with one facing the Moon and one opposite.

Consequently, the thinnest part of Pluto's crust "should" be either at the sub-Charon point or the anti-Charon point. So it's a pretty good conjecture that Tombaugh and Sputnik are at the anti-Charon point because that's where the thinnest crust settled. But it's still a conjecture.

Posted by: Charles Astro Sep 27 2015, 09:46 PM

I agree with JRehling, the location of Sputnik Planum is probably no coincidence. Though that may not help to decide between impact or internal volcanism triggered formation of Sputnik Planum.